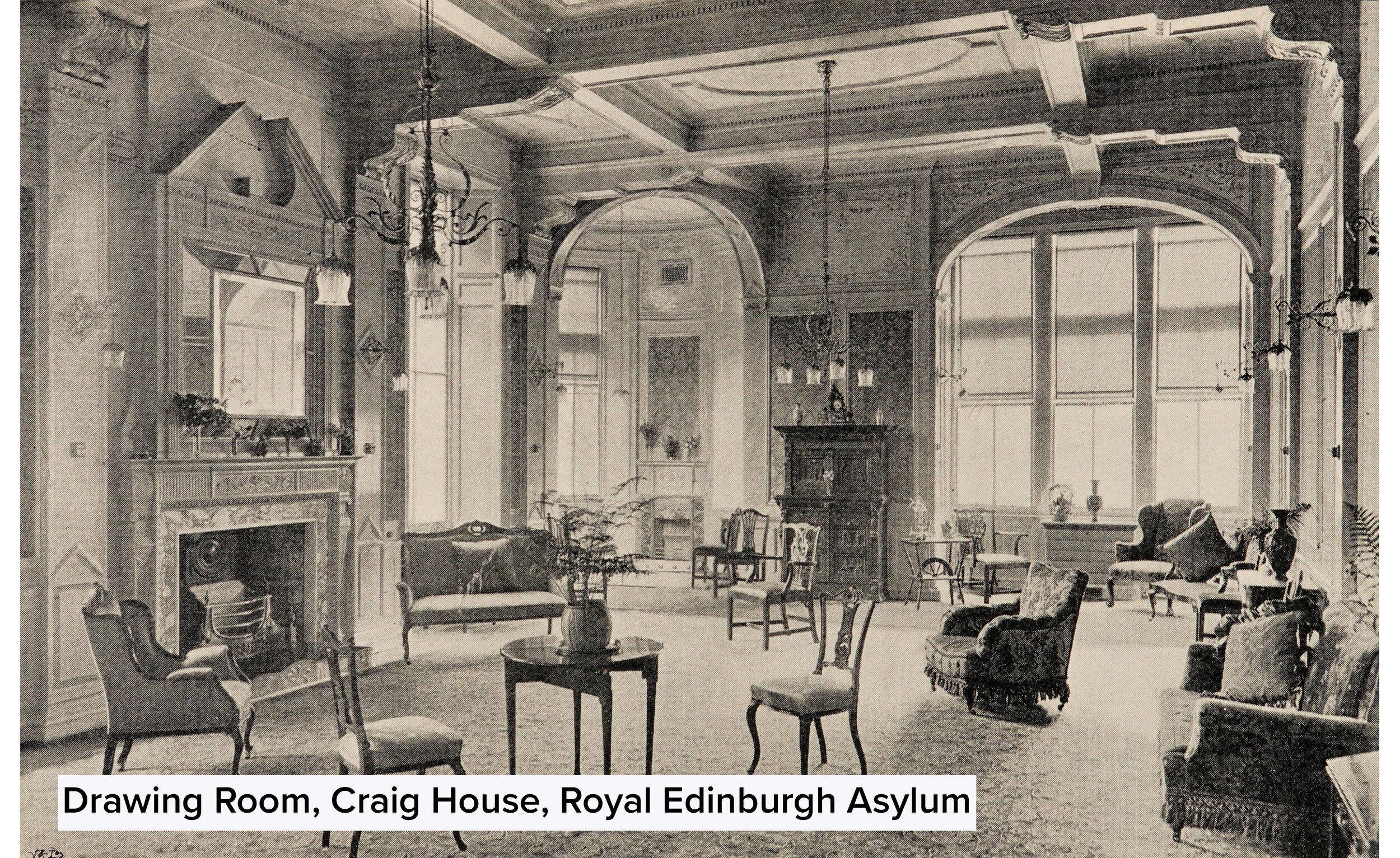

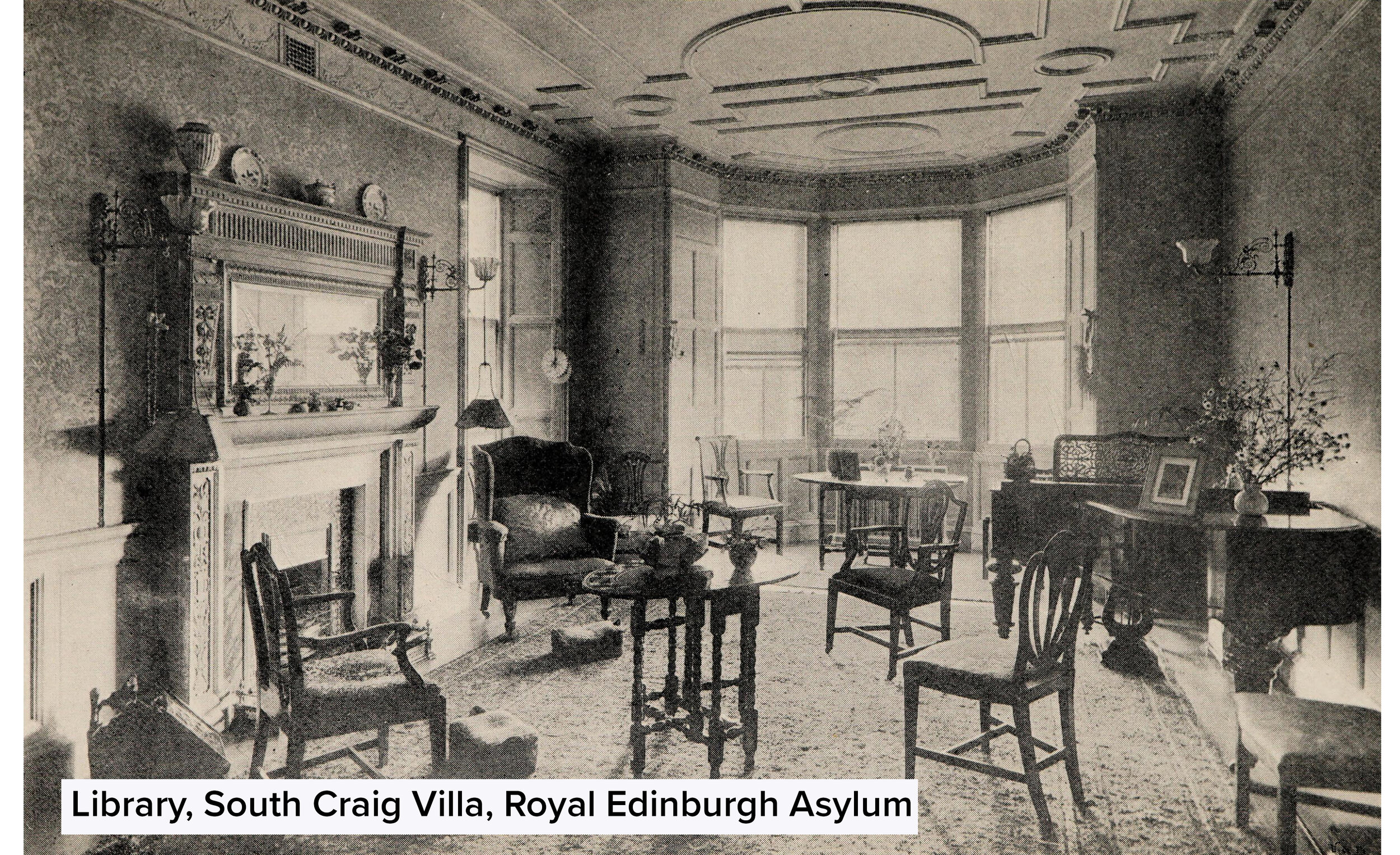

When it came to providing suitable reading for their patients, the Scottish Royal asylums took a relatively traditional approach. Fiction made up the biggest proportion of the libraries at the Crichton Royal Asylum, the Royal Edinburgh Asylum and the Murray Royal Asylum. Religious texts formed a smaller proportion (around half that of fiction at the Royal Edinburgh and the Murray Royal), flanked with scientific texts, works on travel and geography, and history. Biographies formed a signficant part of the libraries too - about 7% on average. These texts offered patients many ‘respectable’ individuals upon whom they might model their own lives. Featured were reverends, writers, and royals: from Bunyan to John Knox to Charles II. Many of these were classics, likely bought second hand or donated from the bookshelves of benefactors of the asylums. However, sitting amongst the more serious texts of the catalogue are a few racier additions to the patients’ reading material. These characters were certainly not examples for patients to follow, so how did they come to be in the library?

Bampfylde Moore Carew, by John Faber Jr after Richard Phelps. Mezzotint, 1750 (NPG D1226, (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

The Murray Royal Institution - The Life and Adventures of Mr. Bampfylde Moore Carew, commonly called the King of the Beggars (1782)

This book, first published in 1745, recounts the life of Bampfylde Moore Carew, an English ‘rogue’. Whilst hailing from a wealthy family, Carew made a name for himself as the ‘King of the Beggars’, spinning tales of (mostly) harmless pranks, tricks, and petty crimes. Beginning with his time at boarding school, where he apparently mastered Latin and Greek alongside making considerable athletic achievements in hunting, the narrative follows a wild life. Joining a band of vagabonds, a trip to Newfoundland, marriage, being crowned ‘King of the Gypsies’, transportation to Virginia, friendship with a group of Native Americans, various escapades across the United States, simulating smallpox to avoid Navy service, and time spent with the ‘Young Pretender’, Bonnie Prince Charlie - all feature in Carew’s narrative. The book was probably not written by Carew himself, and most of the experiences recounted were likely fictional; the researchers at All Things Georgian tracked down some evidence of the ‘real’ Carew which calls into question the authenticity of his claims (aside from the fact of them being hugely outlandish to begin with!) Nevertheless, Life and Adventures was an entertaining read for the eighteenth and nineteenth-century audience and Carew became a notable cultural figure, featuring in print well into the 1800s. It could have been deemed a little fast-paced for the readers of the Murray Royal Asylum - perhaps it was one of the editions which had Carew reflect on his ‘idle’ and unproductive life, in a manner rather incongruous with the rest of the tale, giving it a more ‘moral’ tone.

The Caledonian Mercury reported on Semple Lisle’s defrauding of two women in June 1807.

Crichton Royal Institution - The life of Major J. G. Semple Lisle: containing a faithful narrative of his alternative vicissitudes of splendor and misfortune (1799)

Another interesting autobiography contained in a patient library was held at Crichton, which offered its patients James George Semple Lisle’s own account of his life, written and published during a stay at Tothill Fields prison in Middlesex. The book might have had a familiar tone for asylum patients, as ‘wrongful confinement’ narratives became more numerous during the nineteenth century. It is interesting that Semple Lisle was permitted this luxury whilst in prison. Perhaps surprisingly, Semple describes Mr Fenwick, the prison Governor, as “formed by nature for softening the rigours of captivity.” Semple’s account of his life features his early life, marriage, adventures, affairs, and friendships with European Royals during travels on the continent. However, his fortunes turn. Following an arrest for ‘obtaining goods by false pretenses’ he was sentenced to transportation for the first time, though managed to avoid it. He continued his criminal behaviour, and was sentenced again. His entry in the 1885-1900 volume of the Dictionary of National Biography notes that Semple Lisle went so far as to stab himself and starve himself in attempts to avoid his second transportation. During the journey, a mutiny occurred, and Semple recounts his escape and subsequent travels. This wasn’t his last brush with the law, though - even after another return to England and the prison stay in which he produced his autobiography, he appears in newspaper reports throughout the early 1800s, using confidence tricks to steal money and jewellery from unsuspecting victims across Britain. His Life claimed that “perhaps there exists not another individual who has been so much the play-thing of Fortune as himself,” decrying the “despicable scriblers, who […] have dared to publish their anonymous libels” about him.

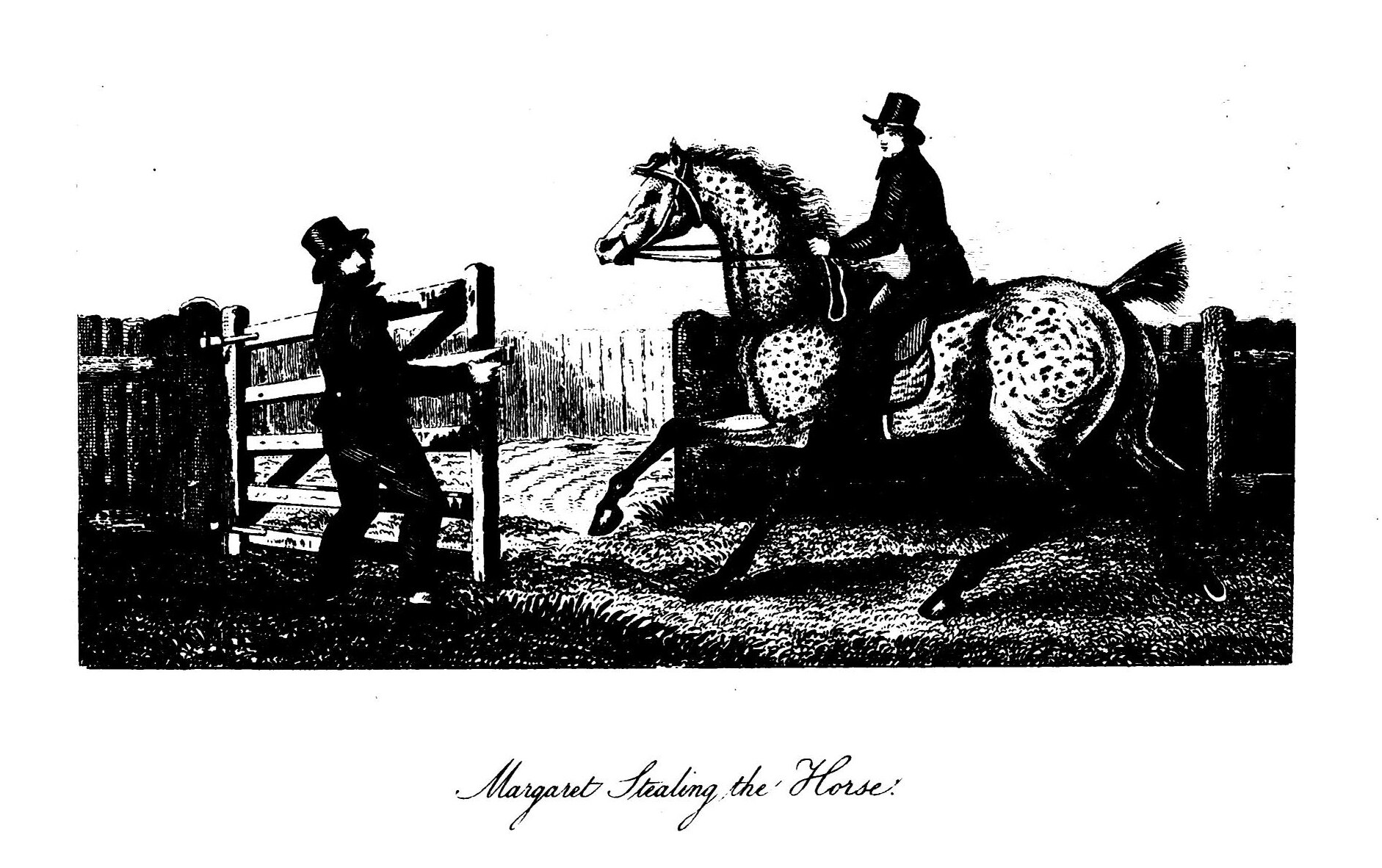

‘Magraret Catchpole Stealing the Horse’, from the 1846 edition.

The Murray Royal Institution - The History and Extraordinary Adventures of Margaret Catchpole, a Suffolk Girl, Richard Cobbold (1845)

A biography rather than an autobiography, The History of Margaret Catchpole was a biographical novel written by Richard Cobbold, featuring transported convict Margaret Catchpole. Cobbold did however have a connection to Catchpole: she was employed by his family in Ipswich, and it was her theft of their horse which led to her being held in Ipswich Gaol, sentenced initially to death and then to transportation. Cobbold paints a picture of a strong, sensible young girl whose fortunes turned. Out of love for an unfortunate sailor-turned-smuggler-turned-navyman, she was persuaded to steal a horse, and was arrested. Her escape from Gaol - impressive considering it required scaling a nearly seven metre tall wall - earned her a second death sentence, and a second commutation, and she was sent to Australia. Here, she flourished, becoming a respectable member of society, eventually working as a midwife and owning a farm. Here, though, is where Cobbold’s story ventures from biography into fiction. Perhaps unable to imagine his heroine unmarried post-redemption, he has her marry the virtuous man whose affections she previously spurned in England; they have a son; and she dies aged 68 with her son by her side in 1841. Cobbold’s maths isn’t quite right on several points, and evidence suggests that she actually died unmarried, in 1819. Cobbold declared that her story was instructive of the “necessity of early and religious instruction,” and that without these, even the cleverest would not be able to “resist the temptations of passion” which might lead to “great crimes as well as great virtues.” Cobbold’s tale was a cautionary one, far more so than Carew or Semple’s works - and this is probably why it ended up on the shelves of the asylum library at the Murray Royal.