During the pandemic many of us have been given a rare insight into the homes of our friends and colleagues via the magic of video calling. We might be surprised by an unexpectedly bold paint choice, pretend not to see the drying washing shoved not-quite-off-camera, wonder just how many of us have the same IKEA wall unit. The choices we make - or the choices we’re unable to make - in our home decor have taken on new significance. One aspect of presentation has come under particular scrutiny during the pandemic: book organisation.

“The book backdrop is both a handy representation of symbolic knowledge, a marker of cultural cachet and a source of analysis for those seeking to understand the particular individual who occupies the foreground.”

Salman Rushdie gives us a long, sombre bookcase thundering past like a great goods train filled with credibility. His dome is bathed in the glow of understanding. A lamp pops brilliantly in the distance. Salman's lesson is that thought illuminates fact. Without it, all is murky. pic.twitter.com/AAMxQJaP0y

— Bookcase Credibility (@BCredibility) July 17, 2020

Long before Coronavirus necessitated these digital meetings, there was a clear sense that books meant something, as David Beer neatly summarises. It’s the reason why job sites suggested that having your books on display during a video interview might not be a good choice, or why we often see ‘experts’ of various kinds interviewed in front of a backdrop of shelves (real or not). In 2017 the Senate Press Gallery had a false bookshelf created by gluing book spines to a dark background, used as a backdrop by Senators during TV interviews; Dominic Raab was ridiculed across the internet following his somewhat conspicious windowsill display during a BBC interview in 2019. Since lockdown began, there has been a wider discussion of the meaning of the bookshelves lurking in the back of our meetings, from serious debate about the contents of Michael Gove’s, to the more lighthearted ‘Bookcase Credibility’ Twitter account. The New York Times dubbed the ‘credibility bookshelf’ ‘quarantine’s hottest accessory’, and Curbed shared images of bookcases ‘carefully selected to look sufficiently realistic’ for use as Zoom call backgrounds. Book historians have been glued to the discussion - and so in November we have a whole conference dedicated to the topic, run by the Open University.

All of this discussion about the conscious presentation of books got me thinking about my own research. What was the nineteenth-century approach to ‘bookcase credibility’? Though books were becoming more accessible to the everyday person, they certainly weren’t as ubiquitous as they are in homes today. Take a working-class home like that of Pearl of Days author Barbara Farquhar, for example, where reading material was collected with a ‘take what you can get’ approach due to financial and geographical restraints. How would Farquhar’s family be judged by their bookshelves? Moving the discussion into the lunatic asylum complicates matters further.

Earlier in the nineteenth century, the asylum was conceived of by many as a domestic space - a household headed up by the Superintendent, and the patients requiring discipline and guidance like children might. Asylum interiors began to reflect these notions of domesticity, and the setup of the interior space was believed to assist in producing ideal patient behaviour. Despite changing approaches to asylum treatment as the century wore on, by the early twentieth century many asylums still retained some of their domestic character.1

Henry Oxley Stephens, Superintendent of the Bristol Lunatic Asylum, admitted in 1863 that some might doubt the impact of the trappings of Victorian domesticity on the insane, ‘especially of the humbler classes’, who wouldn’t necessarily have access to ‘pictures, vases, flowers, singing birds, &c.’ in their own homes.2 However, the Commissioners in Lunacy provided an answer in their own report, which Stephens quotes: these objects ‘serve to engage their attention, occupy their thoughts, and exercise them in habits of care and self-control.’ This is much the same rationale used by some asylum staff to justify encouraging patients to read, teaching them literacy from scratch, and giving them access to quality books.

“The Commissioners in Lunacy, on their recent visit, mentioned that “in the Acute wards there was rather a scanty supply of books, &c.,” and suggested that the issuing of a number of volumes in good condition, instead of “old and well-worn ones,” would have a good moral effect, and that the destruction of books (which had caused the scanty supply) would cease.”

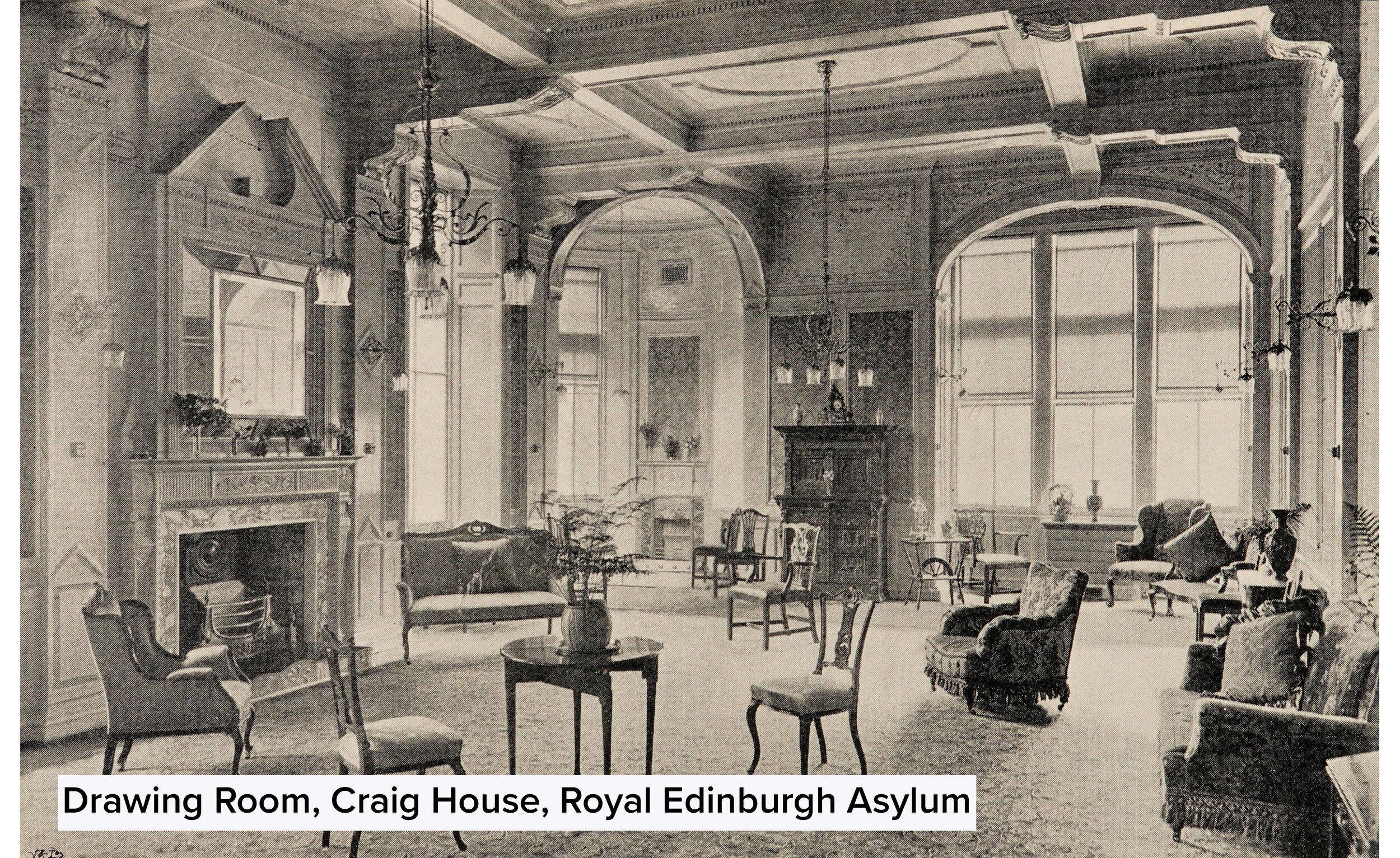

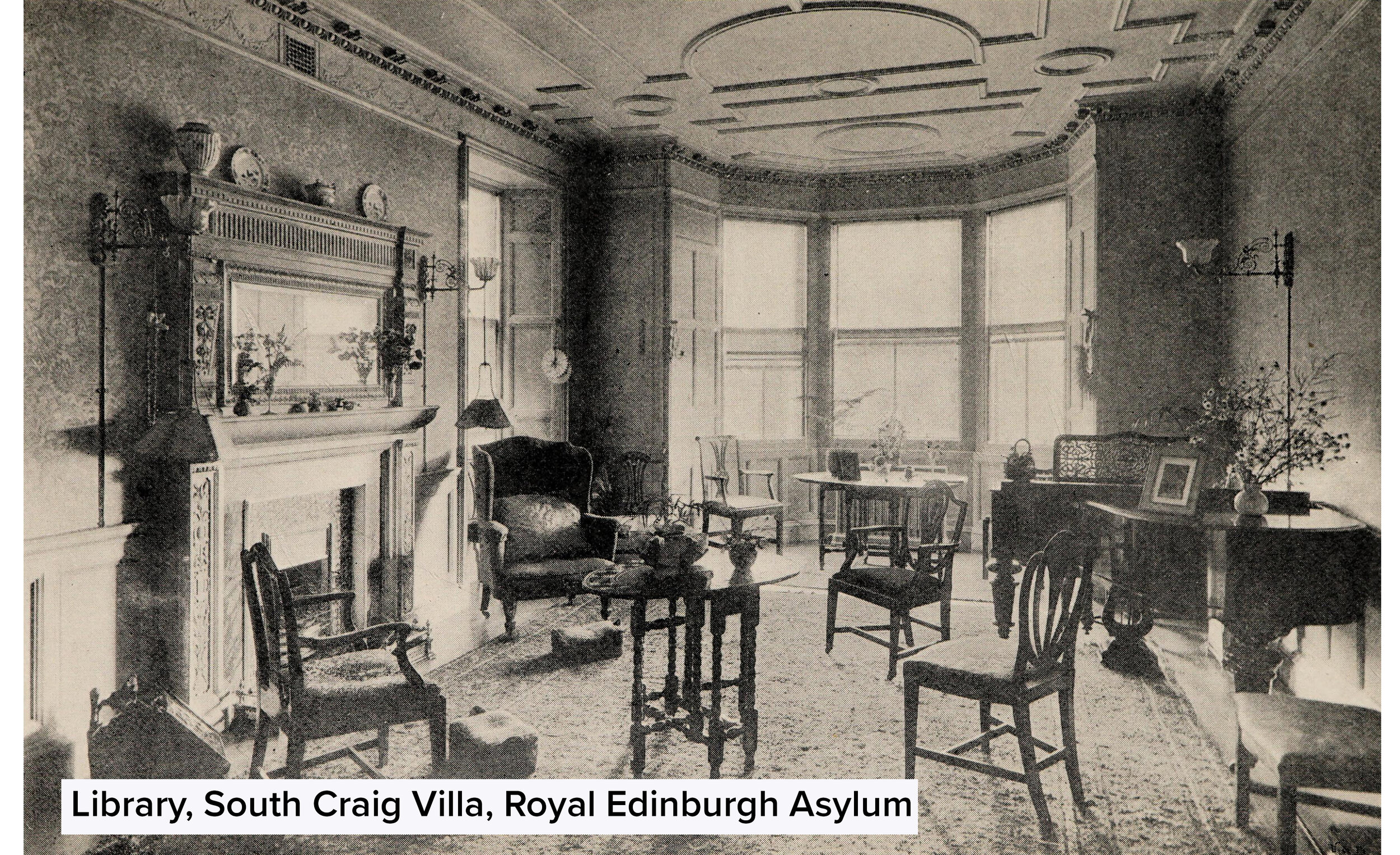

Images of asylum interiors provide some amazing insight into choices made for the patients’ environment. Spaces, particularly those for middle and upper class patients, were often highly decorated and filled with the ‘objects of interest’ as advocated by the Commissioners. These images present a clean, tidy, domestic institution, punctuated appropriately with potted plants, framed pictures, and ornaments, and in classic late Victorian fashion, often a number of chairs verging on hazardous. In many ways, the interiors are like those which might be found outside the asylum. For instance, take the drawing room of Terregles House near Dumfries, photographed by John Rutherford of Jardington in 1889. Rutherford also took many photographs of the Crichton Royal Institution.

Images of asylums were almost always produced at the behest of the institution itself, published in annual reports, or even reproduced as postcards. Their agenda was presumably to present the asylums in a positive light, and to challenge presumptions of dark and cheerless interiors filled with gloomy patients and inattentive staff. They present the ‘ideal’ asylum. In the same way that some of us might curate our backdrops on Microsoft Teams to convey to others our legitimacy, intelligence, or values (or to avoid them being obvious), these images aimed to cement specific ideas of the asylum in a viewer’s mind.

As books formed part of this domestic environment - and since staff were often so keen to emphasise their provision - one might expect to see reading material among the mix. Yet in late-nineteenth century images of the Royal Edinburgh Asylum, even in spaces for wealthy patients, they are conspicuously absent. By this point the asylum must have had a considerable library, growing from a catalogue of over 1500 volumes at the start of the 1860s; yet the room marked as the ‘Library’ of the South Craig Villa does not have a single book visible (see the third image in the slideshow below). The lack of books in these photographs raises two questions: where are the books, and why were they apparently excluded from the recreational spaces photographed?

Rutherford’s images of the Crichton Royal Institution’s main spaces paint a similar picture to those produced of the Royal Edinburgh’s: the dormitory, corridors, dining room, and recreation hall are bare of books. However, images of more intimate spaces, such as the women’s sitting rooms, provide the first visual proof of the existence of reading material within the asylum walls. Two photographs of the same sitting room from Rutherford’s collection give a better understanding of the process of creating these images. The obvious change is the unknown woman in the second shot, but other differences are visible. The placing of framed photographs is altered slightly; an ornament on the sideboard is turned to face the opposite direction; an armchair and cushion are removed; the book is exchanged for another. Clearly, small details matter.

Two views of a lady’s sitting room, Crichton Royal Institution

“[...] it is proposed to supply the wards with a small glazed book-case, fitting with a simple lock, and to provide each patient who desires it, and is able to take charge of it, with a key, thus enabling one to take a book out for perusal when wanted, and to put it back again when done with.”

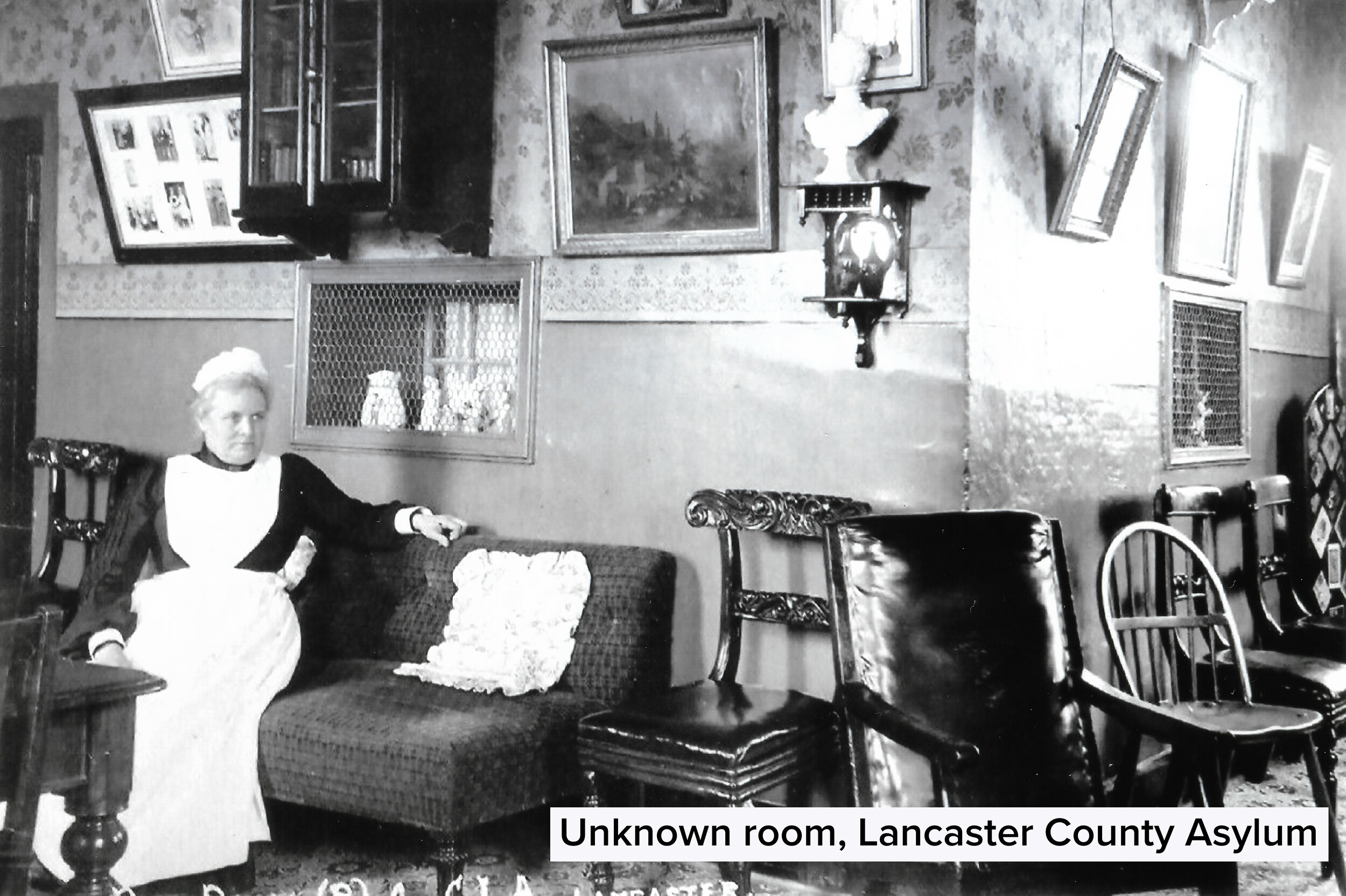

These images reveal the staging decisions made by the photographer (or perhaps an assisting member of asylum staff) in representing this space. Staging was likely applied to many, if not most, images created of asylum spaces in the period. It is a crucial reminder that these representations likely do not show the rooms as they would truly have looked whilst in use by patients, and it also perhaps explains why books are not seen in so many images. Though it is often mentioned in reports that books and periodicals are placed throughout the asylum for patients to look at, they were likely tidied away for the purposes of a staged image where each object was consciously chosen for display. In addition, whilst each asylum had a slightly different approach to storage and distribution, the bulk of patients’ reading material seems to have been kept elsewhere, in rooms not photographed - such as an old Attendant’s room at Bristol in 1890. Instead, it became common for small bookcases (often under lock and key) to be situated in the wards, forming a ‘circulating library’ of sorts. These are often visible in images from other asylums: the small lockable bookcase above a female attendant at the Lancaster County Asylum, filled with small volumes; the ornamented bookcase at The Retreat’s house in Scarborough; or the built-in case featured in a room likely belonging to the Montrose Lunatic Asylum.*

Unfortunately, even with enhancement, the images aren’t detailed enough to ascertain which books were chosen for display in bookcases in these images; a level of analysis like that faced by Michael Gove isn’t possible. Instead, the books included in these images, especially on the rare occasions they are positioned outside of a case, take on a symbolic and cultural meaning more like that described by David Beer. They reflect less on the asylum’s inhabitants (for they usually had little input in reading choice) and more on the values of those who were in command of the institution - or at least the values they sought to project.

Sources:

1 Jane Hamlett, At Home in the Institution: Material Life in Asylums, Lodging Houses and Schools in Victorian and Edwardian England, pp. 19-28.

2 Henry Oxley Stephens, Medical Superintendent’s Report, Report of the Committee of Visitors for the Lunatic Asylum for the City and Council of Bristol, for the year 1863, pp. 9-10 (digitised by the Wellcome Library).

3 James Fountaine, Chaplain’s Report, Report of the Committee of Visitors for the Lunatic Asylum for the City and Council of Bristol, for the year 1897, pp. 16-17 (held by the Glenside Hospital Museum, Bristol).

4 W. G. Davies, Chaplain’s Report, Twelfth Annual report of the Joint Lunatic Asylum at Abergavenny, for the year 1864, p. 20 (digitised by the Wellcome Library).

Images:

An interior corridor at Craig House, Royal Edinburgh Asylum, c. 1897 (Eighty-fifth annual report of the Royal Edinburgh Asylum for the insane: for the year 1897, digitised by the Wellcome Library)

Mrs Maxwell’s room at Terregles House, photographed in 1889 by John Rutherford of Jardington (Dumfries and Galloway Archives and Local Studies DGH1/8/1/2, digitised by the Wellcome Library)

Carousel 1: all at the Royal Edinburgh Asylum, c. 1897 (Eighty-fifth annual report of the Royal Edinburgh Asylum for the insane: for the year 1897, digitised by the Wellcome Library)

The Drawing Room, Craig House

The Great Hall, Craig House

The Library in South Craig Villa

Two views of a lady’s sitting room at the Crichton Royal Institution, photographed by John Rutherford of Jardington, c. 1890s (Dumfries and Galloway Archives and Local Studies, DGH1/8/1/4, digitised by the Wellcome Library)

Carousel 2: various

An unknown room at the Lancaster County Asylum, late Victorian or Edwardian (print bought from a private collection)

The Smoke Room at Throxenby Hall, Scarborough, used by patients at The Retreat, Yorkshire (Borthwick Institute for Archives, the University of York, RET/1/8/9/1, digitised by the Wellcome Library)

Unknown room, likely at the Montrose Lunatic Asylum. *This photograph was found among others, some identified as representing Montrose Lunatic Asylum; it is presumed to belong to this set but is not explicitly indicated as such. (University of Dundee Archive Services, THB 23/19/5/20, photographed at the archive)