This is the second part of a two-part post: read the first here.

Many of the ideas promoted by nineteenth-century asylum doctors are ones which today we recognise to have some truth in terms of improving our wellbeing. It seems a common sense idea that having access to a good diet, education, outdoor space, meaningful occupation, and time for recreation and leisure, might provide a positive impact on our wellbeing. It’s easy to see how legitimate frustration around the current system might lead to a temptation to romanticise systems of the past. In Britain, people can wait months or even years to access therapy, which is often inadequately short-term, even for those with long-term and complex mental health problems. There are instances of children forced to travel hundreds of miles from their families to receive treatment. Between 2007-8 and 2016-17, mental health beds in England were cut by 40%. At the same time, an estimated 1 in 4 people will experience mental health problems over the course of their lifetime; suicide remains the second leading cause of death globally for people aged 15-29.1

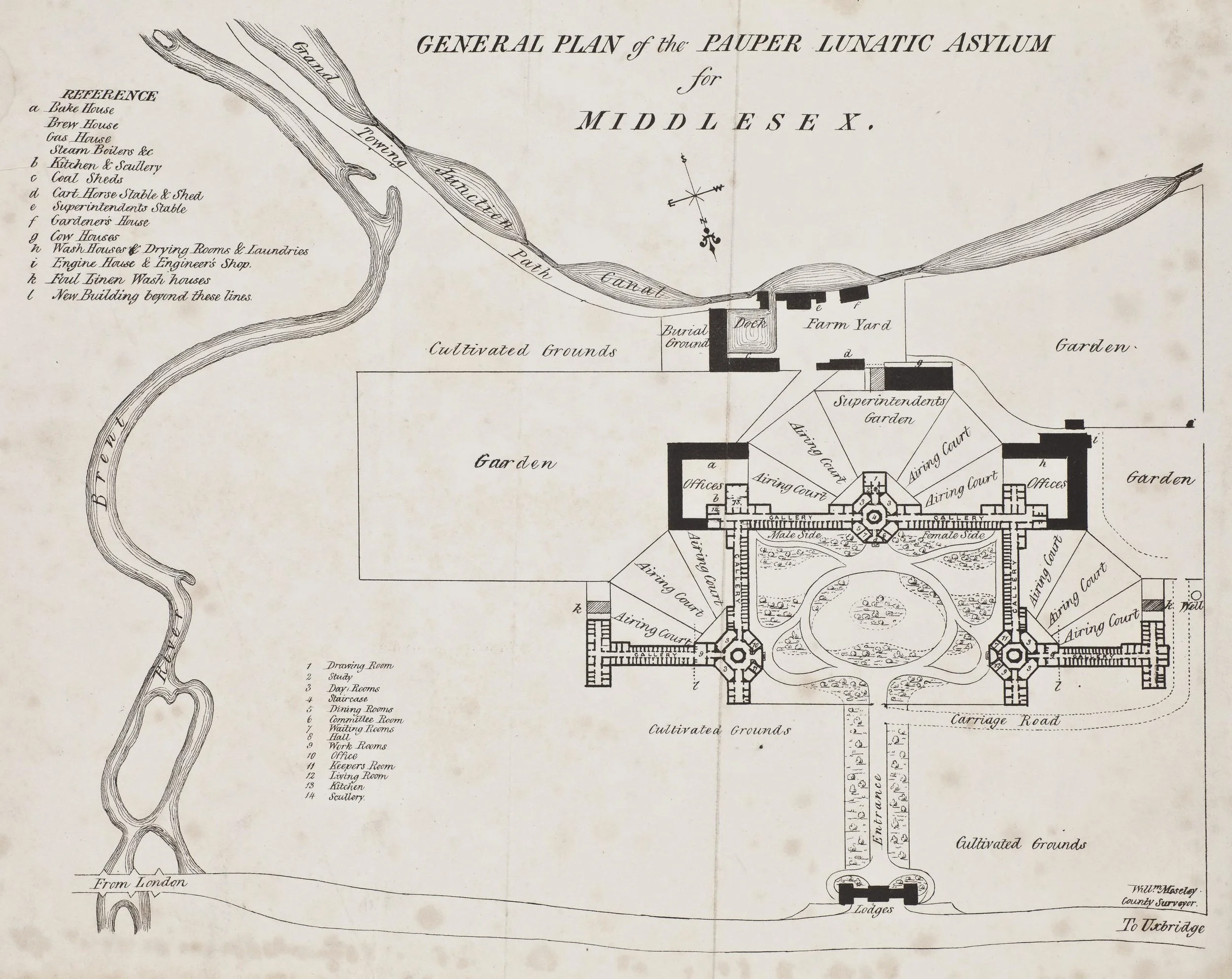

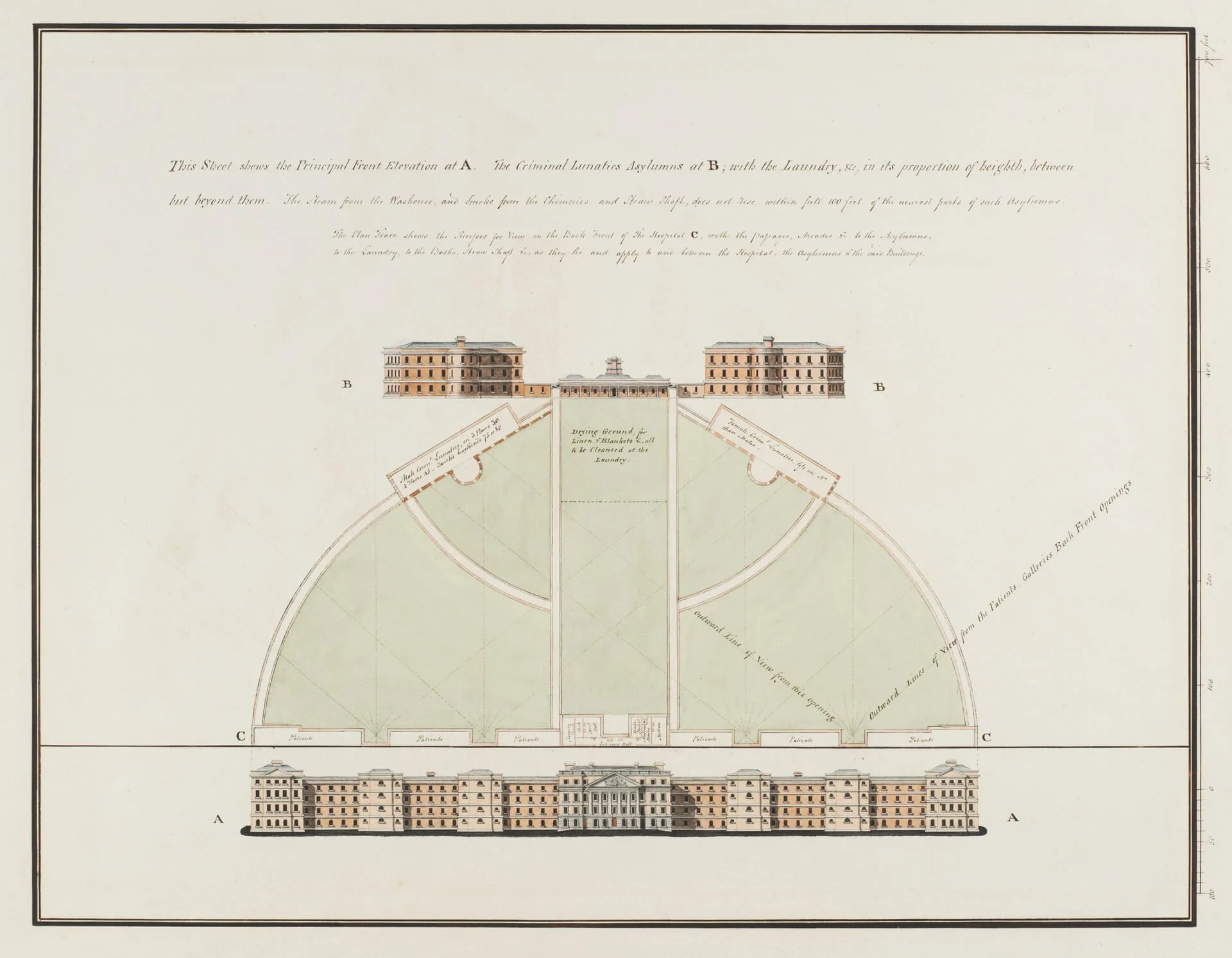

In this context, the idea of an ‘asylum’ - a safe place of refuge, which provides us with the care we need to recover, without the incredible financial cost which comes with private healthcare, can easily seem appealing. The Wellcome Collection’s 2016-17 exhibition ‘Bedlam: the asylum and beyond’ (produced in partnership with South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, the Maudsley Charity, Bethlem Gallery and Museum and the Adamson Collection Trust) questioned this original ideal, and asked whether it might be reclaimed in some way. The exhibition examined the history of psychiatric care, with emphasis on the importance of including those with lived experience, especially visible through the inclusion of patient artwork. Closing the exhibit was Madlove: A Designer Asylum, produced by artists The Vacuum Cleaner and Hannah Hull, in collaboration with Benjamin Koslowski, James Christian and Rosie Cunningham, and over three hundred people with experience of mental health issues. Madlove reimagined a ‘safe place to go mad’ - and to me it was notable that many aspects which people today believed could be helpful for their mental health, and treatment, were also considered essential to the ‘ideal’ asylum back in the nineteenth century.

It’s important to note here that the author of the tweets which inspired these posts represents a service user network, and also tweeted that part of the basis for these tweets was discussion with elderly service users, who communicated their positive experiences within an institutional environment and disappointment with current services. Listening to service users themselves is an essential and often neglected part of mental health treatment, as well as its history.2 These tweets represent an aspect of studying the history of mental health treatment which is essential to consider - how should we use and interpret evidence? Who do we listen to, and who should we listen to, when we are writing our histories? How do we represent contrasting experiences, and discuss those experiences without erasing others?

Whilst the author of the original tweet discussed in the first part of this post was correct on a surface level, and the aspects which were highlighted could be helpful for those dealing with mental health issues, the less romantic reality of the asylum system was entirely obscured. Those ‘grand old mansions’ were often bare, draughty, and cold, and became increasingly overcrowded as the nineteenth century wore on. Whilst some physical treatments such as electro-convulsive therapy and lobotomies didn’t yet exist, other painful and uncomfortable ‘therapies’ were used alongside the more palatable aspects of moral treatment. The ‘rotary motion machine’ or ‘Cox’s chair’, was popularised by Joseph Cox, physician and owner of the Fishponds Asylum in Bristol. Cox introduced the practice of ‘swinging’ patients. Initially, this practice had produced a more natural rock or swing, but Cox aimed for his contraption to induce vomiting and nausea, as well as attempting to ‘shock’ the patient to their senses.3 Cold water was used as treatment and sometimes punishment. In the patient magazine of the Murray Royal Asylum in Perth, one patient wrote that a cold water treatment used at the Sussex County Asylum "involved the most decided and most objectionable form of Mechanical Restraint which we have encountered in any part of the world!”4

Nimmo & Mackintosh detail their use of blistering on a patient, 19th Annual Report for the Dundee Royal Lunatic Asylum, 1839.

So-called ‘depletive’ therapies were frequently utilised, especially at the beginning of the century. Bloodletting and blistering were commonly resorted to. Blistering involved the use of irritants such as mustard powder or powdered Spanish fly to produce blisters on the patients’ skin, usually the head or neck. William Smith, a patient at the Royal Edinburgh Asylum, avoided the usual bloodletting but had leeches applied to his eye for a bout of conjunctivitis, as well as receiving a blister.5 Patrick Nimmo, Physician, and A. Mackintosh, Superintendent, even partly credit blistering for the recovery of a patient at the Dundee Royal Asylum in around 1838.6 Mary de Young’s Encyclopaedia of Asylum Therapeutics notes that whilst this practice was largely abandoned by the mid-nineteenth century in Britain, it was used for far longer in Colonial asylums as ‘both a counterirritation treatment and as a punishment’.7

“We are far too apt to forget the relation between mind and body, to consider the former as apart from, and independent of, the latter – only to recognise the transmission of physical deformities, whilst it is well known to those who have undertaken such investigations, that not only these, but mental and moral defects are equally transmissible, or appear in descendants in other forms, as talents, aptitudes, genius, vices, or peculiarities.”

Fundamentally, aside from the brutal treatments used by asylum doctors, most of the patients came to the asylum against their will. They were at the mercy of asylum authorities, who decided when they would be able to leave. An obsession with the ‘hereditary taint’ of insanity led doctors to discuss the merits of allowing those deemed ‘insane’ to reproduce.8 W. A. F. Browne, who advocates empathetically for moral treatment (including games, books and sports) describes one woman as a ‘squinting, hideous, dirty, drunken imbecile’, and puts forward the fact that she is still at ‘liberty’ and having children as evidence that the authorities are not eager enough to seclude ‘lunatics’.9 Many of the most ‘enlightened’ asylum doctors who promoted moral treatment were also deeply invested in theories such as phrenology, which have resulted in untold social harm; some of these myths persist to this day and remain used to defend white supremacy.10 The entire system - theory, diagnosis, treatment - and its practitioners were steeped in misogyny, racism, ableism and eugenicism. The asylum system can only be romanticised when its context is removed.

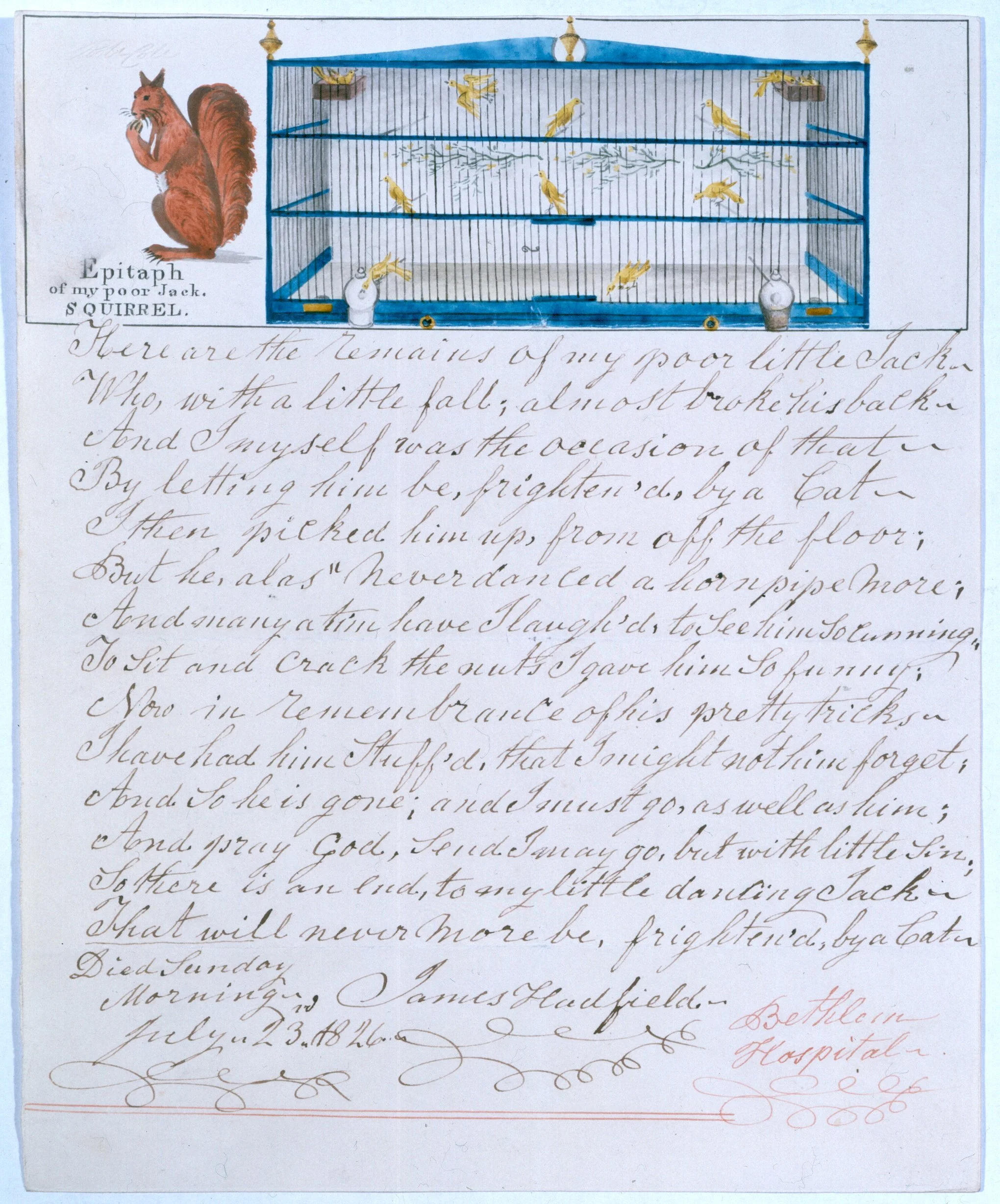

In my research, I aim to work with first-person accounts of asylum life wherever possible. Some patients write of very positive experiences within the asylum environment and credit it for their recovery; others considered it a prison. Largely, and understandably, the experiences of the latter group of patients have been instrumental in constructing the ‘patient view’. My research engages with a side of asylum life which could be deemed a ‘positive’ aspect of the system - the power of reading to ‘soothe the soul’ or cheer us up is something which most book lovers would consider themselves familiar with, and it seems to have been a lifeline for some patients. Reading provided a link to their families, to their homes, to the wider world, as well as a purposeful activity, mode of distraction or joyful entertainment. It’s important to me that all experiences of patients, both positive and negative, are considered and valued (a point which the author of the tweet thread in question emphasises.) However: I don’t want my research to be used support a romantic view of asylums, or seen as an apologia for the institutional system. I’m grateful to the author of that tweet for making me think more carefully about the wider purpose of my research and to anticipate how it might be perceived and used.

Expanding and complicating our understanding of the history of mental health care - its failures and successes - is essential in forging better paths for the future. We can, and need, to do better than twenty-first-century mental healthcare; but we don’t need to go back in time to do so.

Sources:

1 Mind’s ‘We Still Need To Talk’ report on access to talking therapies, published in 2013, still remains relevant to issues of access today.

2 Roy Porter’s ‘The Patient’s View: Doing Medical History from Below’, Theory and Society (1985), pp. 175-198, is an essential text in foregrounding the fact that all medical encounters involve two parties - doctor and patient - and that the experience of the latter is often obscured in the history of medicine.

3 See Nicholas Wade et al, ‘Cox's chair: 'a moral and a medical mean in the treatment of maniacs', History of Psychiatry (2005), pp. 73-88, and Sheila Dickson, ‘Rotation therapy for maniacs, melancholics and idiots: theory, practice and perception in European medical and literary case histories’, History of Psychiatry (2018), pp. 22-37.

4 Excelsior, No. 36, January 1876, p. 4. (University of Dundee Archives Services, THB 29/12/1/1).

5 Case notes of William Smith (Lothian Health Services Archive, LHB 7/51/1, March 1840 - September 1842), p. 180.

6 Nineteenth annual report of the directors of the Dundee Royal Asylum for Lunatics (Dundee Advertiser Office, 1839), p. 29.

7 Mary de Young, Encyclopaedia of Asylum Therapeutics (McFarland, 2015).

8 Eighth Annual Report of the Inverness District Asylum, for the year ending May 1872 (Highland Archive Centre, Inverness, HHB/3/2/1/3), p. 14.

9 Second Annual Report of the General Board of Commissioners in Lunacy for Scotland (Thomas Constable, 1860), p. 198 (Highland Archive Centre, Iverness, HHB/3/19/1/1).

10 Tom Whyman’s article for The Outline, “People keep trying to bring back phrenology”, covers some of the current attempts to defend ‘race science’ and the phrenological logic of AI facial recognition.