In a previous post I’ve talked a little about the nineteenth-century asylum being something of an anomaly when it comes to the public perception of asylums. In culture and media, stereotypical elements of pre- and post-ninteenth-century treatment are merged to create the asylum’s defining characteristics, and we tend to think of lobotomies, electro-convulsive therapy, or chains. But some tweets I saw recently swung the pendulum to the other side, to a perspective I see far less often: romanticisation.*

The thread opened:

Continuing, the author added that patients weren’t locked up; they were encouraged to go outdoors, and engage in activities such as crafts and gardening; they were allowed to smoke, and to keep pets. The kind of asylum life described in the tweet thread is more in keeping with nineteenth-century asylums, rather than twentieth-century asylums which patients alive today would remember. But these aspects of the nineteenth-century asylum system are actually accurate - at least on a surface level - and they are things I remain surprised by as I undertake the research for this project.

Asylum managers were encouraged to equip the wards with means of entertainment - bagatelle boards were a regular feature, and were highly encouraged by the Commissioners in Lunacy, such as at the North Wales County Asylum in 1871.1 Some asylums had billiards tables, though usually for the wealthier patients. Books and periodicals, as my research examines, were considered an essential feature of a well-run asylum. Patients were absolutely encouraged to spend time outside - institutions built in this period were often situated in the countryside, and asylum authorities spent considerable sums on landscaping, providing covered walks, even ornamental gardens. Throughout 1878, visiting Commissioners in Lunacy who visited the Inverness Asylum complained of the ‘bare’ appearance of the grounds, repeatedly instructing the managers to plant trees and shrubs in order to improve the gardens and to provide shelter to patients walking in rain or sunshine.2 Claire Hickman’s work on the visual experience of asylum landscapes is particularly interesting, as she highlights the therapeutic potential of viewing the landscape alongside its use as a recreational space.3

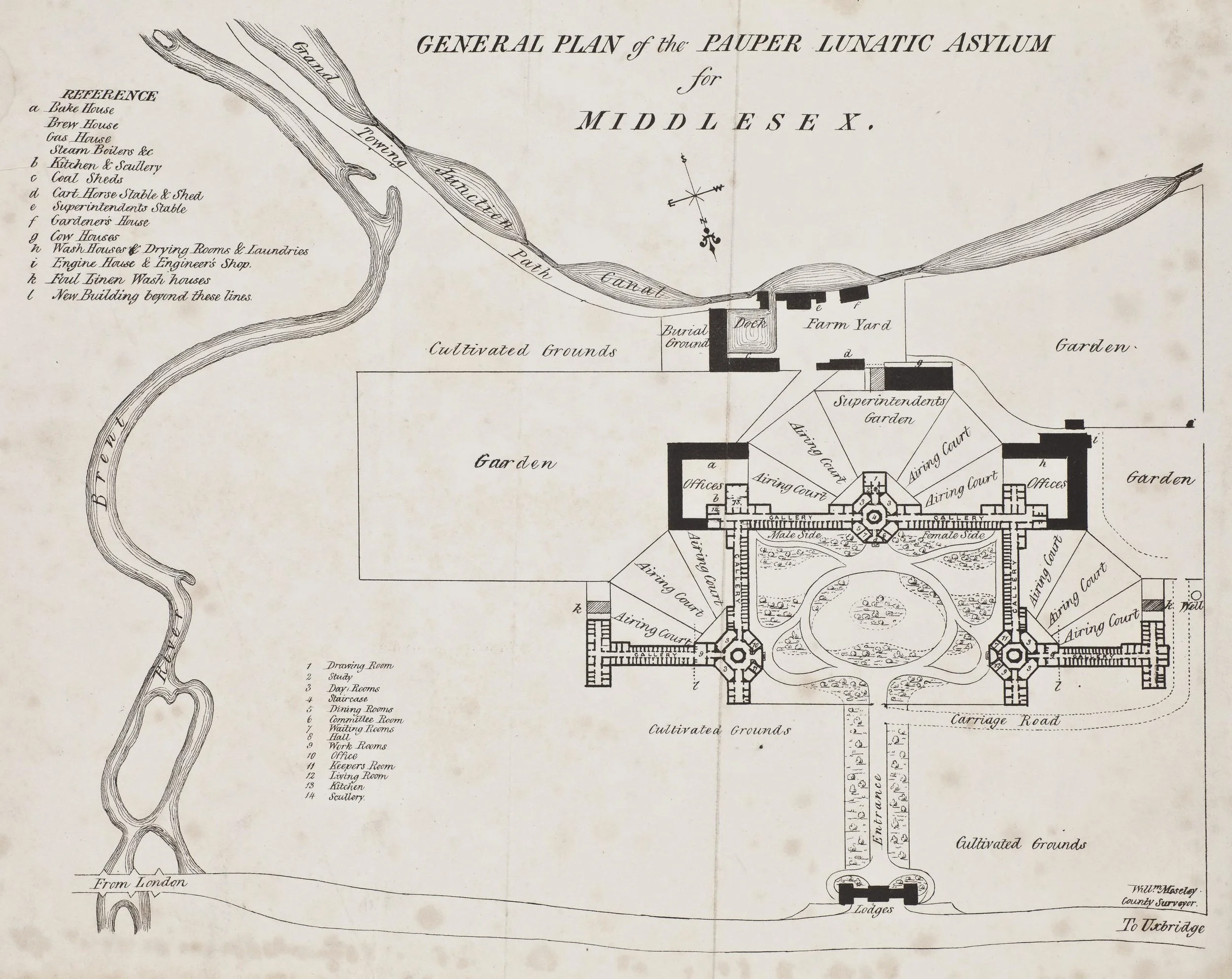

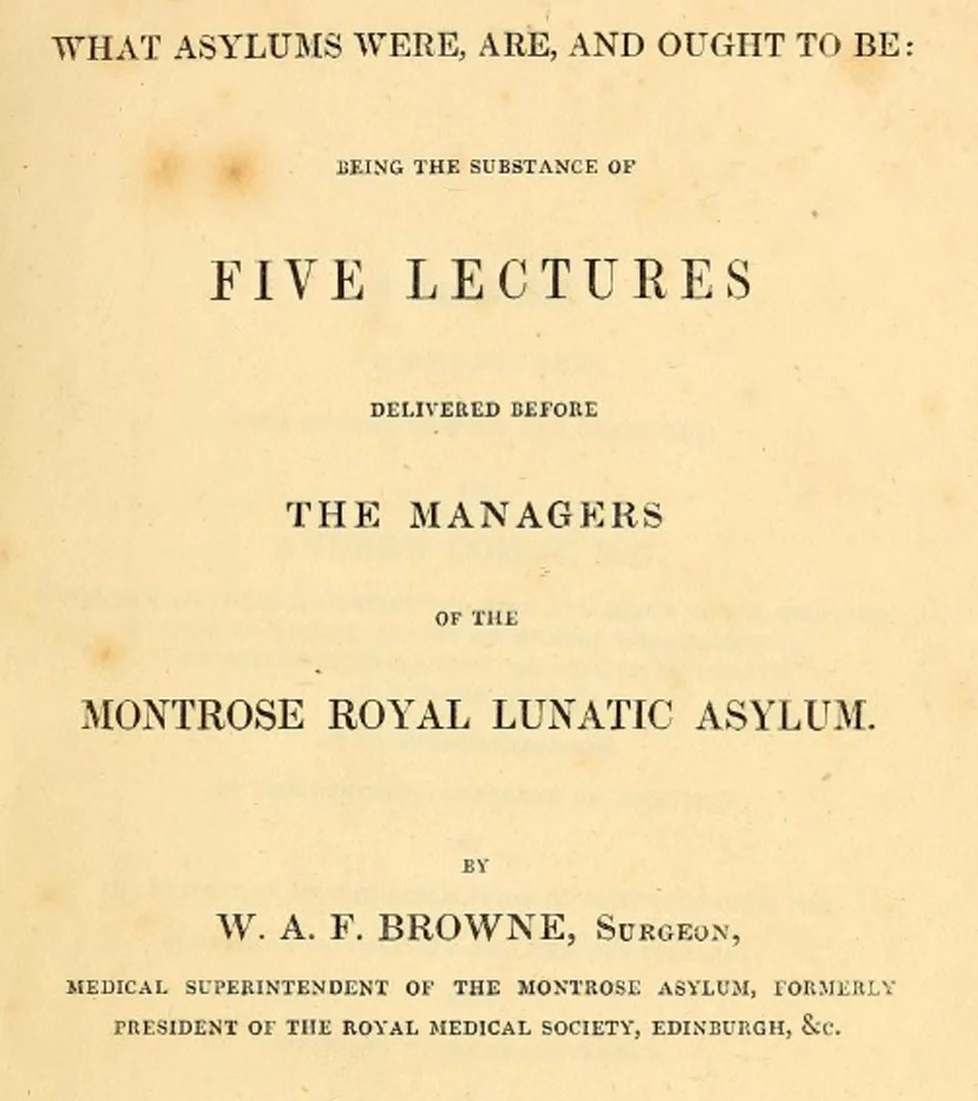

A large part of the outdoor space in many asylums was made up of farmland, which many patients would work on. This became a key part of patients’ activities under the moral treatment regime. W. A. F. Browne wrote in his description of the ‘ideal’ asylum that ‘Gardens, grounds, farms, must be attached to each establishment, and must be cultivated by or under the direction of lunatics.’4 Vegetables, meat, milk, and even beer were produced in the asylum, and many became semi-self-sufficient. William Ellis, Superintendent at Hanwell Asylum in London, describes the agricultural activity of the asylum in his Treatise on the nature, symptoms, causes, and treatment of insanity in 1838. There is an ‘abundant’ supply of vegetables, meat from the pigs and milk from the cows, and the entirety of the bread and beer are produced in-house.5 In many asylums, tobacco was provided to patients who worked outdoors as a reward for industriousness. Patients at the Birmingham Asylum, originally housed in London asylums, complained to the Commissioners in 1897 that the amount of tobacco they were allowed in exchange for working was smaller than in London, and the Commissioners agree that this seems unfair.6 Beer was regularly given to patients as part of their diet, sometimes with extra given to those working outdoors. Birmingham Asylum set up a brewery in 1854, to supply patients and staff with their regular allowance.7

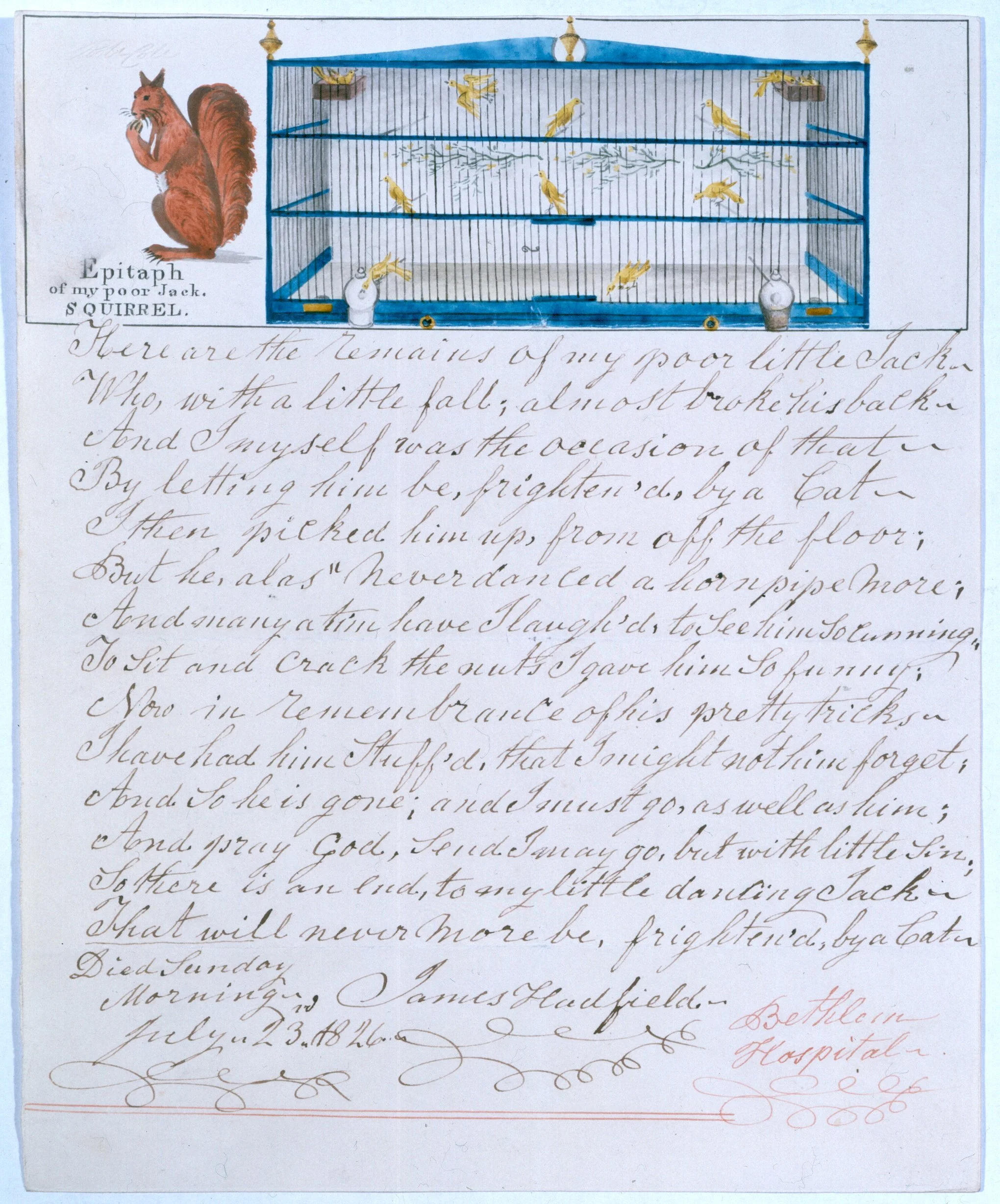

James Hadfield, Epitaph of my poor Jack, c. 1834 (© Bethlem Museum of the Mind)

The cheering influence of animals was well acknowledged, and this blog by Lesley Hoskins at Pet Histories explores the significance which relationships with animals could hold for patients. At the Glasgow Royal Asylum, gulls were introduced into the airing courts for the men;8 the Murthly Asylum in Perth kept goldfish;9 and Commissioners in Lunacy who visited asylums repeatedly suggested the addition of singing birds. The Crichton Royal Institution had a veritable zoo of their own, including squirrels, jackdaws, owls,10 and even tortoises.11 James Hadfield, held at Bethlem for trying to assassinate King George III, had several pets: two dogs, three cats, several birds, and finally his squirrel, Jack. He apparently also preserved his pets as taxidermy specimens.12

“Pets occupy the leisure time of others. Another lady has succeeded in securing the confidence of a robin to such an extent as to induce it to feed from her hands in the grounds. To our usual stock we have to add a cargo of tortoises, recently received.”

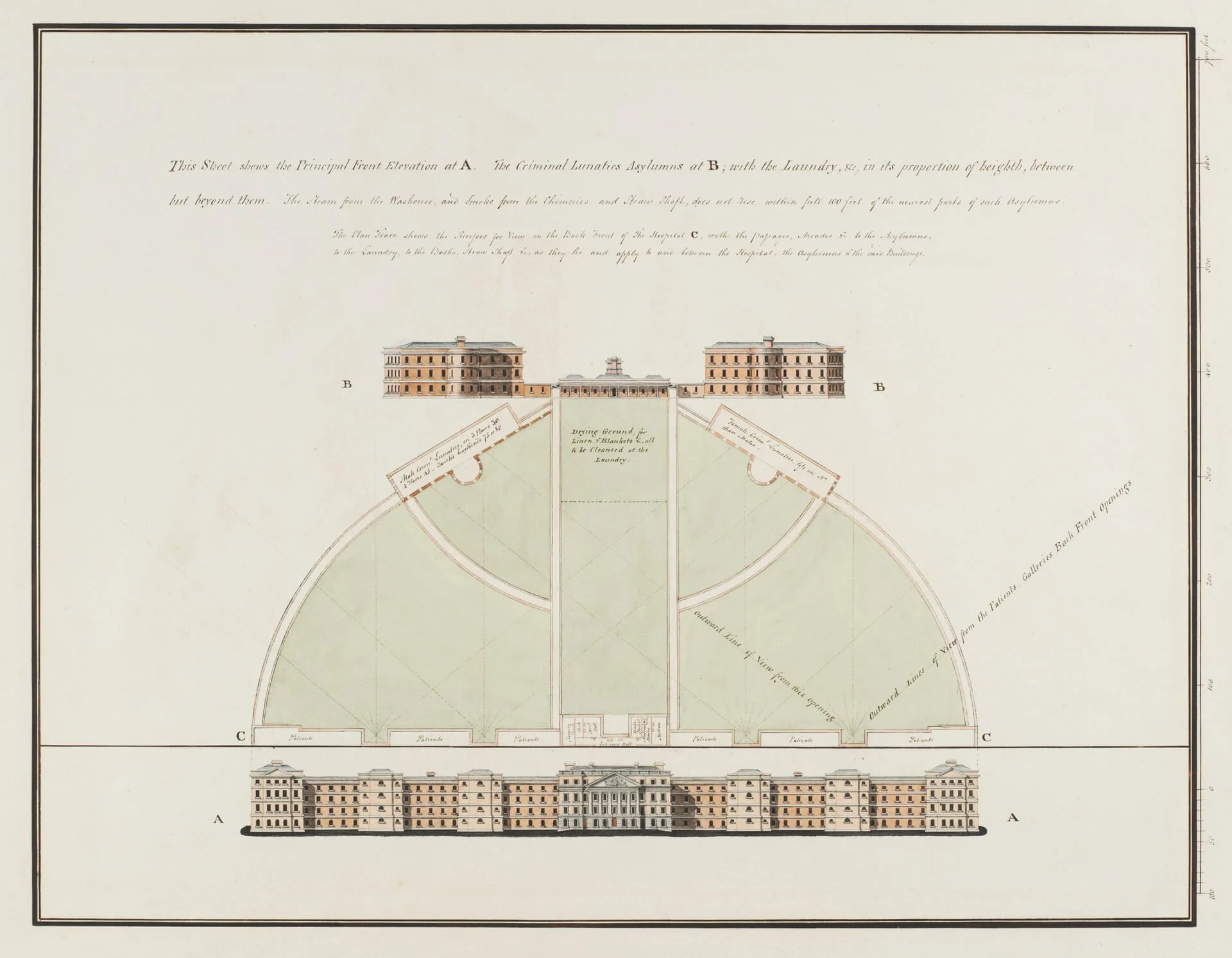

Some patients of the period, envisioning the ‘ideal’ asylum, produced plans including features rather like those discussed above. James Tilly Matthews was a patient at Bethlem, institutionalised for his belief that he (and others) were being subjected to torture and mind control via a machine called the ‘Air Loom’, and his case became well known through John Haslam’s publication Illustrations of Madness. Matthews’ family and several doctors argued that he was sane, and he was eventually moved to a private asylum. However, whilst he was a patient at Bethlem, he produced detailed architectural plans to submit to the public competition held by the Governors in 1810 to find a design for the new building. The forty-six pages of research and drawings (which earned him an unofficial £30 prize) detailed some of his ideas for the asylum: that patients should be allowed to grow vegetables, help with chores, and look after other patients.

James Tilly Matthews’ plan for Bethlem, 1810 (© Bethlem Museum of the Mind)

Discussing Bethlem in her chapter ‘Bedlam: fact or fantasy’, Patricia Alleridge draws attention to the way that Bethlem was often used as a ‘reach-me-down historical cliche’, a recognisable image often used to ‘fill in odd gaps in the picture’. ‘The reading public’, she writes, ‘seems preconditioned to accept that if it is bad enough, it is bound to be true.’13 The realities of asylums are more complex than even many historians make clear - Alleridge contrasts the cases of Matthews and James Norris. Norris was the famous case of a man who had been chained for years, which condemned Bethlem as a place of brutality. Whilst Norris was chained in an undoubtedly appalling fashion (largely due to the asylum authorities’ inability to deal with his extreme violence), he was also encouraged to read, and had a pet cat. He was also a patient at the same time as Matthews, who was drawing, writing, and even publishing from Bethlem. Norris has garnered much attention, whilst Matthews is rarely discussed - largely because one fit the stereotype of Bedlam, and the other does not. Alleridge is correct when she writes that:

“A Bethlem that contains both [Norris and Matthews], together with all the gradations in between, is likely to make a more rewarding subject for study, and to tell us more about, for example, attitudes to the insane, than a Bethlem dedicated to brutality and inhumanity as its sole policy.”

It is worth considering the often less-discussed aspects of asylums, and many historians have produced excellent work engaging further with wider aspects of the asylum system since Alleridge’s chapter was first published in 1985. In the wider public, however, the tendency to slip into a dichotomy remains. In the second part of this post, I’ll discuss some of the things this tweet thread glossed over, and how I see my own research fitting into the puzzle.

* The author has since partially deleted this thread as a result of criticism for it, so I won’t link to their account or the tweets themselves. The tweet pictured here via screenshot no longer exists.

Sources:

1 The Twenty Third Annual Report of the North Wales Counties Lunatic Asylum, Denbigh: for the year 1871 (William Hughes, 1872), p. 8.

2 Commissioners in Lunacy Patients’ Book, 1873-1893 (Highland Archive Centre, Inverness, HHB/3/2/2/2).

3 Claire Hickman, ‘Cheerful prospects and tranquil restoration: the visual experience of landscape as part of the therapeutic regime of the British asylum, 1800-60’, History of Psychiatry (2009), pp. 425-441.

4 W. A. F. Browne, What asylums were, are, and ought to be, (Adam and Charles Black, 1837), p. 192.

5 William Ellis, A treatise on the nature, symptoms, causes, and treatment of insanity (Samuel Holdsworth, 1838), p. 304-5.

6 Report of the Visiting Committee of the Lunatic Asylum for the City and County of Bristol (J. W. Arrowsmith, 1898), p. 7 (Glenside Hospital Museum).

7 Report of the Committee of Visitors of the Lunatic Asylum for the Borough of Birmingham (Benjamin Hunt & Sons, 1855), [for the year 1854], p. 7.

8 Seventh Annual Report of the General Board of Commissioners in Lunacy for Scotland (Thomas Constable, 1865); visit to Glasgow Royal Asylum, 14th May 1864, p. 166 (Highland Archive Centre, Inverness, HHB/3/19/1/3).

9 Seventh Annual Report of the General Board of Commissioners in Lunacy for Scotland; visit to Murthly Asylum, Perth, 30th July 1864, p. 179 (HHB/3/19/1/3).

12 Flora Tristan, Promenades dans Londres (Flora Tristan’s London Journal), trans. by Dennis Palmer and Giselle Pincetl (George Prior, 1980), via Yale Center for British Art.

13 Patricia Alleridge, ‘Bedlam: fact or fantasy’, in Anatomy of Madness: Essays in the History of Psychiatry, Volume II: Institutions and Society, ed. by W. F. Bynum, Roy Porter and Michael Shepherd (Routledge, 2004) (first published 1985).