Back in 2016, a post which featured an image listing various reasons for admission to the Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum in West Virginia went viral on social media. Among the more usual suspects such as the death of family members, injuries sustained through war, and venereal disease - ‘novel reading’ was listed. These ‘reasons for admission’ are more accurately the situation which caused the mental illness with which patients were diagnosed, rather than the sole reason for their admission - but it shows how reading could be considered injurious to a person’s mental health to the point of requiring institutionalisation. Roy Porter gives other examples: a woman named Sarah Oakey was admitted to Gloucester Asylum with melancholia due to novel reading; John Daft supposedly drove his mind ‘morbid’ through reading too much Carlyle.1 However, if reading the wrong things in the wrong way could have a powerful negative effect on the mind, it stands to reason that reading the right things in the right way might be able to produce positive results, too.

Men reading at Bethlem Hospital. The Hospital of Bethlem [Bedlam], St. George's Fields, Lambeth: the men's ward of the infirmary. Wood engraving by F. Vizetelly, 1860 (Wellcome Collection CC BY)

This was the thought that appealed to many asylum practitioners. Under moral treatment, patients were to be taught discipline, self-improvement, and given moral guidance by asylum staff. Books, with their powerful influence over the mind and morals of a reader, could therefore became an ideal addition to the alienist’s arsenal. Samuel Tuke, grandson of the founder of the York Retreat, encouraged reading (especially ‘useful knowledge’) as a form of amusement but specifies that ‘works of imagination’ and anything connected to a patient’s delusions would be ‘decidedly objectionable’.2 Asylum keeper George Man Burrows likewise encouraged controlled reading. He believed that ‘nervous’ patients could induce hypochondria in themselves through reading, and blamed the periodical press’ reporting on coroners’ inquests for normalising suicide and describing successful methods.3 This is an issue the press remains criticised for; the Samaritans now provide guidelines for the reporting of suicides.

At Colney Hatch Asylum in 1857, Superintendent W. G. Marshall takes a more lenient view. Reading shouldn’t be simply an informative pursuit; rather, it is a primary means of entertainment, aiding in providing a ‘homely’ atmosphere and engendering patients’ positive feelings towards their treatment.4 It also had the additional benefit of calming patients down, presumably appreciated by the staff. The Royal Edinburgh Asylum’s David Skae sees reading as a socially and morally acceptable form of amusement, labelling it as a ‘constant source of intellectual improvement and recreation’.5

“[Books] solace many a discontented and dejected spirit, to place the deluded and misanthropic in connection with real events […] and even more directly to act the part of a remedy, for whenever the judgement can be brought to receive and derive interest from the contemplations of other and these healthy minds, it is less attentive to, and less actuated by its own suggestions.”

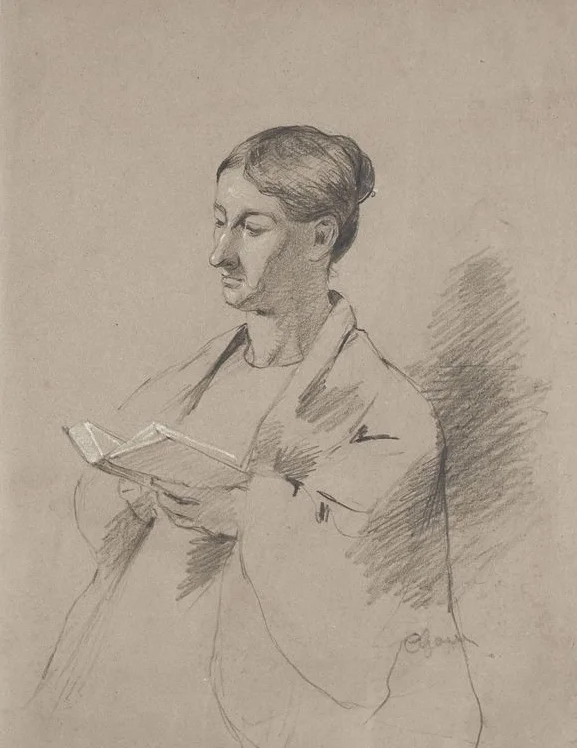

Anne Campbell, Bethlem 20 May 1841, ‘monomania with pride’, illustration by C. Gow (Royal College of Physicians Edinburgh, RCPE Artefacts DEP/MOR/4/95) - with thanks to Isla Macfarlane, whose work brought me to this illustration.

W. A. F. Browne, Superintendent at Crichton Royal Institution, writes at length about the activities of the library, and provides perhaps the most enthusiastic endorsement of the power of reading. Browne’s reports encapsulate the potential that some practitioners felt reading offered not just as a casual activity, but as part of a mode of treatment: it is ‘as expedient’, Browne writes, ‘to bestow care upon the Library as upon the Laboratory’. Lists of patients soothed by the Library occur regularly: the ‘silent, solitary being’ who consistently steals books from other patients to have enough to read; the man plagued by delusions of persecution ‘laughs merrily over Harry Lorrequer’; the ‘well-educated gentleman’ over-applying himself to the ‘severer studies’ of Greek and Hebrew persuaded to learn French instead; the suicidal patient ‘seduced into temporary forgetfulness of his woes’ through translating Guizot and Vertot; the ‘reveriest’ who was ‘tempted from his dream, and from his corner and carpet’ through the provision of his favourite literature.6

My PhD project seeks to examine the wider views of asylum practitioners from across Britain and Ireland; to establish how these views (along with external factors) were framed as medical directives for patients; how reading was facilitated for patients within the asylums; and how patients experienced print culture within the walls of their institutions.

Sources:

1 Roy Porter, ‘Reading is Bad for your Health’, Longman/History Today Lecture (1998) - available online.

2 Samuel Tuke, Description of the Retreat (Isaac Pierce, 1813).

3 George Man Burrows, Commentaries on the causes, forms, symptoms, and treatment, moral and medical, of insanity (Thomas and George Underwood, 1828).

4 W. G. Marshall, ‘Medical Report of the Female Side’, Annual Report of Colney Hatch Asylum, 1857.

5 David Skae, ‘Physician’s Report’, Annual Report of the Royal Edinburgh Asylum, 1852.

6 W. A. F. Browne, ‘Physician’s Report’, Annual Report of Crichton Royal Institution, years 1839-1845.

![Men reading at Bethlem Hospital. The Hospital of Bethlem [Bedlam], St. George's Fields, Lambeth: the men's ward of the infirmary. Wood engraving by F. Vizetelly, 1860 (Wellcome Collection CC BY)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ba9158c7fdcb8e5c8f1ce0f/1548258824414-ZEWTGDTSESVDFVUSXY9C/Male+patients+reading+at+Bedlam%2C+1860+%28Wellcome+Library%29)