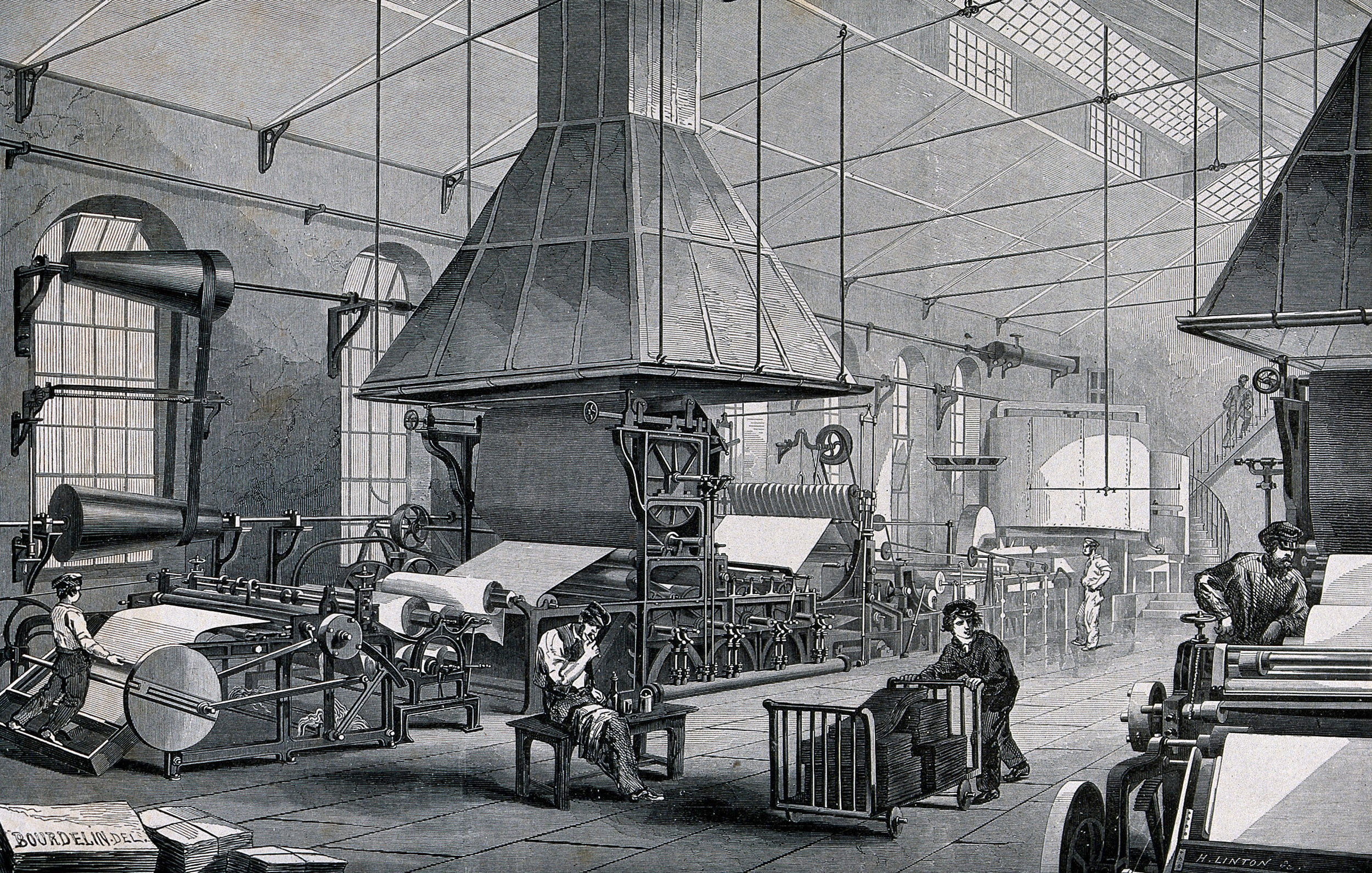

A mechanized, shaft-driven printing-press. Wood engraving by H. Linton after E. Bourdelin, mid-1800s. (Wellcome Collection CC BY)

The nineteenth century witnessed an explosion of technological advancements, and for print culture this signalled some of the most important developments since Gutenberg brought together the elements required to create the printing press in around 1450. New iron printing presses were developed, giving greater stability in printing and allowing the introduction of steam power to vastly speed up production times. Processes for creating metal type, previously relying on hand labour, were automated. Paper could be made at greater quantities and far faster than before. After a £1000 reward was offered by The Times in 1854 for a cheap alternative to rags, esparto grass provided less expensive - though lower quality - paper throughout the nineteenth century (experiments using wood pulp, today’s most recognisable paper ingredient, were ongoing).1

William Johnson Neale, The Captain’s Wife (Routledge Railway Library, 1862), digitised by Emory University Libraries.

It wasn’t just printing-related technology which impacted the trade: the railway system was instrumental in spreading printed material across Britain. Trains could heavy printing machines, metal type, or large amounts of paper. Metropolitan papers could now reach across the country in a timeframe where they were still relevant, and provincial presses could be set up to serve local areas.2 As commuting increased, passengers also needed entertainment: this provided a greater demand for newspapers and magazines, and cheap entertaining books for longer journeys. W. H. Smiths became a household name through their railway news stands, beginning in Euston and spreading across the network - these carried cheaper titles often called ‘yellowbacks’, for their distinctive cover designs.

These factors led to greater production of books, newspapers, magazines and ephemera than ever before. Between 1800 and 1835, twenty-five thousand titles were published in Britain; between 1835 and 1862, this figure more than doubled, at 64,000. In 1801, the number of copies of stamped newspapers was 16 million, but by 1849 newspapers numbered at 78 million. Still, books weren’t cheap enough for everyone to be buying them for their own collections. The ‘triple decker’ novel of the early nineteenth century, published in three volumes, might cost between fifteen and eighteen shillings - over half the weekly wage of a printer, and nearly all of a teacher’s. Even the cheaper yellowbacks weren’t appealing to everyone as a purchase item.

Customers in Mr Mudie’s new hall, from the Illustrated London News, 29th December 1860, p. 619 (Wellcome Collection CC BY)

Readers across Britain were keen to find ways to access printed material, even if they didn’t have the money to purchase themselves. Whilst the term ‘literacy’ has some complicated connotations, the nineteenth century provided a growing literate audience - in part due to the improvement of education provision.3 It can be estimated that around two thirds of men and half of women were literate by 1840, giving an audience of roughly more than ten million.4 Even prior to the establishment of the first public library system, readers had options. Those with a little more cash to spare could join book clubs or subscription libraries. Circulating libraries like Mudie’s often satisfied more ‘popular’ tastes, and offered cheaper subscriptions for varying periods. Philanthropic efforts resulted in libraries for the benefit of the working classes, such as the Mechanics’ Institutes. However, working class readers also pooled their resources to purchase texts of their own choice, setting up reading rooms and libraries within their own communities.5

Whilst widespread literacy today is usually considered a benchmark of an equal and progressive society, historically the idea has proven contentious with those holding societal power. There was concern that giving the working classes access to printed material could educate them above their accepted station, or even inspire revolutionary action. However, utilitarian principles ultimately won out. Wider education could reduce the time that the working classes spent on ‘base’ pleasures and induct them into a more morally disciplined lifestyle, conducive to the wider success of industrial society. An early supporter of the public library system even described it as ‘the cheapest police that could be established’.6

But would reading cure the unruly working classes of their taste for the pub? The reality, as ever, was more complex. Middle class readers devoured ‘sensation’ fiction, gripped by crime and questionable romance; the working classes, whose tastes supposedly tended naturally toward the immoral, frequently sought out the ‘classic’ Literature-with-a-capital-L.7 Readers are notoriously rebellious, and for those who were worried about the public, no one (working class or not) ever seemed to be reading what they ought to be.

Reading for self-improvement might have unintended consequences on your other duties! ‘The rise, and fall, of literature’, T. L. Busby, 1826 (Wellcome Collection CC BY)

Sources:

1 For excellent overviews, see Rob Banham, ‘The Industrialisation of the Book’, in A Companion to the History of the Book, ed. by Simon Eliot and Jonathan Rose (Blackwell, 2007), and James Raven, ‘The industrial revolution of the book’, in The Cambridge Companion to the History of the Book, ed. by Leslie Howsam (Cambridge University, 2015).

2 Simon Eliot, ‘From Few and Expensive to Many and Cheap: The British Book Market 1800-1900’, in A Companion to the History of the Book.

3 The British Library’s explanation of education in Victorian Britain gives a good summary of changes in the nineteenth century.

4 Lawrence Stone, ‘Literacy and Education in England, 1640-1900’, Past and Present, (1969).

5 Chris Baggs, ‘Radical reading? Working-class libraries in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries’, in The Cambridge History of Libraries in Britain and Ireland Volume 3: 1850–2000 (Cambridge University, 2006).

6 Joseph Brotherton in the Parliamentary Debate on the Public Libraries Act, quoted in Alistair Black, Simon Pepper, and Kaye Bagshaw, Books, Buildings and Social Engineering: Early Public Libraries in Britain from Past to Present (Ashgate, 2009).

7 Jonathan Rose, The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes (Yale University, 2001).

Other interesting resources:

Tom Shillam’s post for the National Railway Museum about yellowbacks; ‘The Yellowback: Sensational Stories on the Railways’

Matthew Taunton’s post, ‘Print Culture’, for the British Library