This post is the first in a series, ‘Books of the Asylum’, which will examine some of the titles which are known to have been held in asylum libraries across Britain and Ireland.

Towards the end of 1847, Glasgow-based Evangelical publisher John Henderson announced an essay competition. This was a competition specifically aimed at the working classes, and the aim was to create a body of literature which could be used as proof that the working classes were supportive of Sabbatarian aims, rather than seeing it as simply a secular day for amusement. Henderson announced the competition for working men towards the end of 1847, with prizes of £25, £15, and £10 for the best three essays. By the end of March 1848, 1045 essays had been received. Prizes were won by John Allan Quinton (a printer), John Younger (a shoemaker), and David Farquhar (a mechanic). Yet the most successful entry to the competition was one which was disqualified from it.

‘The Pearl of Days: or, advantages of the Sabbath to the Working Classes’ was widely praised, and sold over thirty thousand copies in the first few months; but it was not eligible for the competition by virtue of being written by a woman, rather than a man. This ‘Scottish Maiden’s Essay’ was authored by ‘A Labourer’s Daughter’, a pseudonym of Barbara H. Farquhar. Farquhar had seemingly anticipated the possibility of being considered ineligible for the competition, as she sent a letter with her entry.

“I have thought it unnecessary to inquire whether a female might be permitted to enter […] The subject of the Essay is of equal interest to woman as to man; and this being the case, I have looked upon your restriction as merely confining this effort to the working classes. Whether I judge rightly or not, matters but little […]”

Farquhar had not, unfortunately, judged rightly. The essay, however, appears to have been the favourite, and its disqualification more a matter of formality. In The Spectator for December 1848 it is described as ‘the prize essay’, and it was even commented on directly by Prince Albert in correspondence to Lord Ashley. Whilst it could not be a prize-winner, it was apparently considered by the judges to be ‘a production which ought not to be withheld from the world’, and it was their duty to humanity, as well as the ‘Labourer’s Daughter’, to have it published independent of the competition essays.

Competition entrants were asked to provide a ‘sketch’ of their life alongside their essays, and Farquhar obliged. Farquhar was Scottish, the daughter of a gardener, and had spent much of her life in domestic service in the family home and that of her father’s master. She had received little formal education, taking turns with her sister to attend a sewing-school over the course of two years; her education was ‘at the fireside of hard-working parents’. At the time of writing, she lived in a small house with her widowed mother, four of her nine siblings, and two relatives, having dealt with significant illness in the family and the death of her father and sister.

Martin Spence notes that in most of the autobiographies received alongside competition entries, authors sought to portray themselves as ‘archetypes of Sabbath-keeping working-class respectability’. Farquhar is no different. The author of the introduction praises her for avoiding ‘the opportunity for and danger of egotism’ which comes with autobiography. Instead, ‘to sink self, and to elevate principles, should be the sole object’. Farquhar uses her sketch, as well as her essay, to promote traditional notions of Victorian domesticity. She presents the ‘ideal’ female figure: companion, friend, and adviser to her husband, and a mother, nurse, instructor and guide to her children. She praises her mother’s belief that it was ‘improper to be bustling about when the father was within’, and that a home was to be a quiet refuge for a labouring husband. This echoes arguments made by those such as James Booth, who presented the example of a ‘young mechanic or artisan’, driven to the gin palace with its ‘good fire and penny newspaper’ by his wife’s inability to provide a neat and tidy home. The principles that Farquhar chooses to ‘elevate’ in her autobiography are clearly that of a respectable, domestic, working-class woman.

Farquhar’s essay presents the Sabbath as an essential day of rest for those whose lives are shaped by ‘severe and unremitting toil’. It is central to the wellbeing of the working classes both physically and mentally, and even as a solely secular institution, a necessary limitation of the power of exploitative employers. Her argument promotes what Spence categorises as the ‘democratic Sabbath’, and holds the ‘radical tinge’ he ascribes to many of these essays. Farquhar does not believe, however, that the Sabbath was merely a day for physical rest. Rather, it should be used for ‘the improvement of ourselves and others in holiness, virtue, and intelligence' – linking cultural and literary progress with spiritual growth.

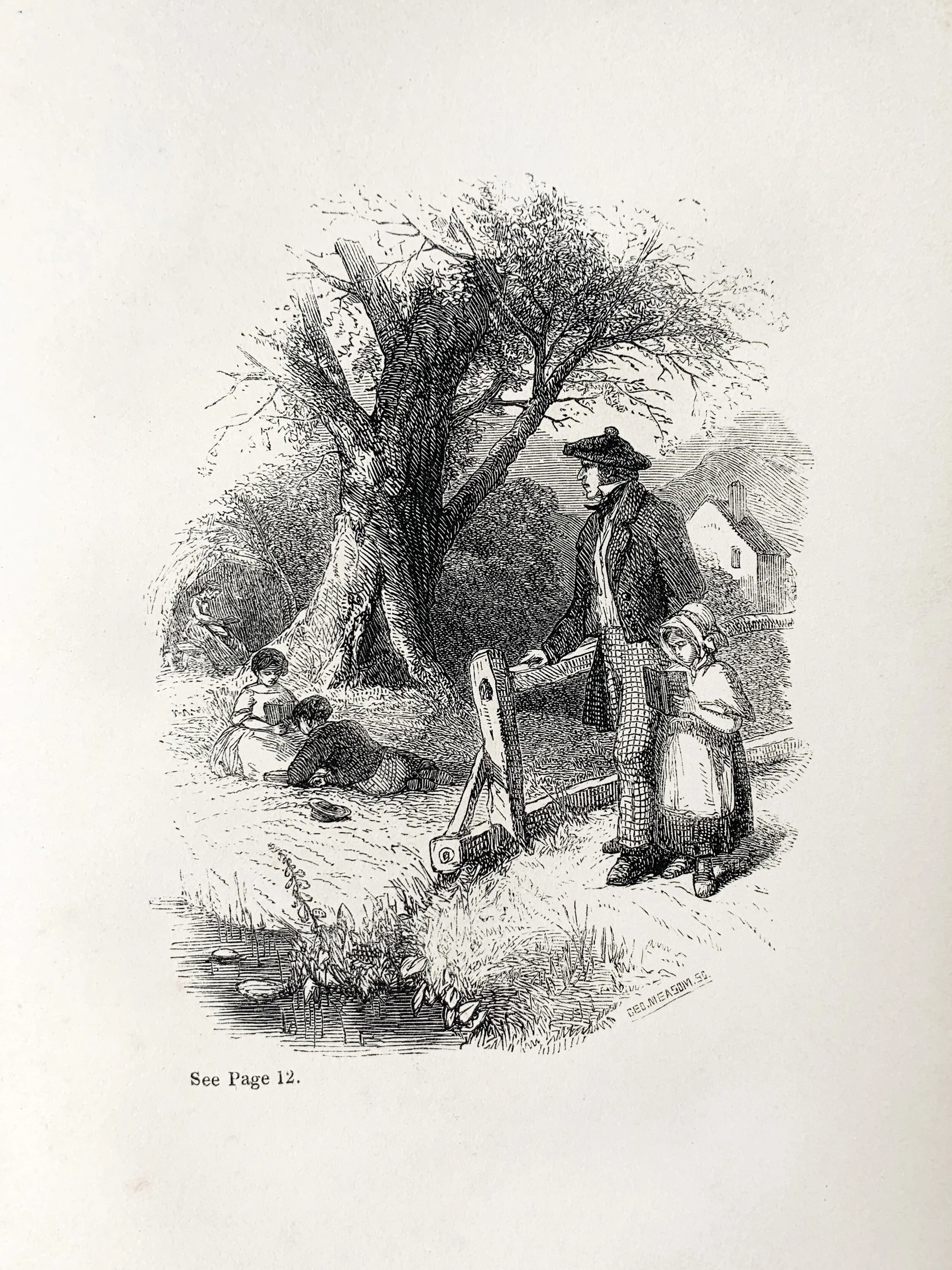

Considering the asylum system’s preoccupation with self-improvement and the development of ‘moral and intellectual powers’, it is perhaps not surprising that The Pearl of Days might be considered an ideal text for an asylum patient. The book was held by the Crichton Royal Asylum in their library, and is listed in the catalogue for 1853. Farquhar’s life as she described it was in many ways the ideal aspired to for asylum patients: a family unit led by caring parents, with teachings ‘calculated to form and strengthen in [children] a habit of self-restraint’; education with the goal of understanding religious teaching better; ‘active and healthful amusement’ and ‘useful and necessary employment’. Interestingly, the book also presents a blueprint for ‘ideal’ reading. She describes in her ‘Sketch’ the importance of reading to her family, accompanied by illustrations of idyllic scenes. Children retire to various spots in the garden to read on the Sabbath, or a woman (presumably the ‘Labourer’s Daughter’ herself) reposes in front of a fire, engrossed in a book and with a cat at her feet. In her essay, she outlines the importance of reading philosophy, theology, and history, and the dangers of ‘exciting’ novels to exhausted minds.

“Our Sabbaths were our happiest days [...] when we would sally forth, book in hand, in different directions, one to stretch himself upon the soft grass in the field close by, another to pace backward and forward on the pleasure walk, or to find a seat in the bough of an old bushy tree; while another would seek a little summer-house our father have made of heather, and seated round with the twisted boughts of the glossy birch, each reading aloud till the allotted lesson was thoroughly fixed upon our minds. [...] During the afternoon, mother would read to us, or all of us, father and mother included, read by turns; questions were then asked, and conversation entered into, about what we had been reading. ”

The relative freedom in their reading could, she admitted, be condemned by some for its ‘laxity’ – but she emphasised that with learning of Scripture underpinning their knowledge, they were ‘led to analyse what we read […] to receive nothing as truth, until it had been put to the test of the Divine word’. But the variety in their reading was often a matter of necessity: without a library nearby, being far from a town or village, and having limited funds, Farquhar’s family largely had to ‘make do’ with the books they could access with their geographical and financial restrictions. A school-book washed downstream in a storm was a ‘prize’ for the children.

This echoes the experience of many working class readers, and also those living within the asylum system, who would have to rely on libraries developed through donation and second-hand purchase. No records exist in terms of borrowing at the Crichton Royal Institution, so we cannot be sure whether asylum patients ever read this text; but is interesting to consider how patients might have related to Farquhar’s mode of living and reading whilst they were in the asylum. The book provides a useful lens through which the subjects of gender norms, class struggle, education and leisure can be examined, especially in the context of ‘ideal’ asylum reading.

Sources:

[Barbara H. Farquhar], The Pearl of Days: or, advantages of the Sabbath to the Working Classes, (London: Partridge and Oakey; Glasgow: D. Robertson, 1849).

Martin Spence, ‘Writing the Sabbath: The Literature of the Nineteenth-Century Sunday Observance Debate’, Studies in Church History, 48 (2012), pp. 283-295.

John Jordan, 'Sabbath Essays by British Workmen', Evangelical Christendom Volumes 3 & 4, (1850), 281-7 .

James Booth, On the Female Education of the Industrial Classes (London: Bell and Daldy, 1855), p. 16.

‘Miscellaneous’, The Spectator, 23 December 1868, Volume 21, p. 1227.

The Crichton Royal Institution Library Catalogue survives as part of a scrapbook compiled by Charles Cromhall Easterbrook, who was Physician Superintendent of the Crichton Royal Institution from 1908 to 1937. C. R. I. Scrapbook, DGH1/6/17/1, Dumfries and Galloway Archives and Local Studies, pasted to p. 16.

Teresa Gerrard and Alexis Weedon, ‘Working-Class Women's Education in Huddersfield: A Case Study of the Female Educational Institute Library, 1856-1857’, Information & Culture, 49 (2014), 234-264 .